Location: Home >> Detail

TOTAL VIEWS

J Sustain Res. 2024;6(3):e240039. https://doi.org/10.20900/jsr20240039

Division of Social Science, Lulea University of Technology, Lulea 97187, Sweden

Drawing from literature across various disciplines, this article aims to provide a fuller picture than what is typically outlined by ‘environmental historians’ regarding the important and consolidating decade of Swedish environmental policy and legislation in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and demonstrates how it in line with expressed needs in the current climate policy debate involved green business and knowledge-based policy implementation. Given the urgency of the interaction between humans and the environment today, it is valuable to revisit previous policy-making practices, knowledge developments, technological solutions, and businesses seeking to reform this interaction. This is particularly justified for countries regarded as environmental forerunners, such as Sweden.

The expanded perspective on environmental concern in Sweden during the late 1960s and early 1970s teaches us that policy action primarily focused on reducing industrial pollution emissions into water and air. Additionally, it prompts us to reconsider environmental concern as something that could grow within business, industry, and government authorities in parallel (and sometimes prior) to public opinion and advocacy by environmental opinion makers. Several Swedish government institutions, along with the industry/government co-funded pioneering environmental research institute IVL, demonstrated significant readiness to discover, understand, and address the growing environmental challenges. During this nascent period of environmental concern, addressing environmental issues often involved targeting low-hanging fruit—relatively straightforward and cost-effective solutions, such as developing measurement standards and devices that significantly benefited various industry sectors.

Sweden is frequently regarded an environmental forerunner and was among the first to establish an Environmental Protection Agency (hereafter SEPA) in 1967, and the extensive Environmental Protection Act (hereafter EPACT) in 1969 [1]. Sweden further hosted the first UN conference on the global environment in 1972. In this article, we argue for a broader perspective than typically outlined by “environmental historians” (including historians of ideas and -science, and political scientists who have contributed to the traditional historical narrative of early modern environmental concern, and which we give a brief overview of in this article) on the important, consolidating decade of Swedish environmental policy and legislation, the late 1960s/early 1970s, and show how it in line with expressed needs in the current climate policy debate involved green business and knowledge-based policy implementation. Since the interaction between humans and the environment remains an urgent and major problem, it is a good idea to sometimes look back to previous policy making practices, knowledge developments, technological fixes, and businesses seeking to reform this interaction, and here historians can contribute a lot [2,3].

The rise of modern environmental concern in the 1960s and onwards ranks among the most seminal topics of ‘environmental historians’ worldwide. Scholars engaged with the topic from a Swedish perspective have typically acknowledged the autumn of 1967 as a national ‘breakthrough’. In this context, references are often made to a chorus of naturalist authors, scientists and journalists arguing for a global environmental crisis in media and books (notably to [4] and [5]), all of this within a national setting where acid rain and mercury poisoning were perceived as particularly pressing environmental hazards [6–11].

While we do not claim that this narrative is incorrect, we align with Uekotter [12], Sörlin and Warde [3], and Melosi [13] in asserting that it largely excludes important elements related to environmental politics, green business, and green knowledge production. Business and industry have long been major contributors to pollution, and many environmental problems necessitate technological solutions. Although this crucial role of businesses and industry (including their engineers) in the overall environmental landscape has attracted business historians since at least the 1990s (who have found the business/environment relationship to be highly varied and complex (see, e.g., [14–16]), these aspects remain severely understudied by environmental historians [12]. Overall, instead of solely focusing on the ideas defining the interaction between humans and the natural environment, we emphasize policy actions, knowledge development, and technological fixes that have sought to influence this interaction.

Regarding further the recognition of the 1960s as the breakthrough for environmental concern, we find it somewhat misleading. As we will demonstrate below, the environmental activities during the 1960s had clear roots in past policies and industrial engagements. They were not limited to an environmental awakening or breakthrough solely among experts and intellectuals. Furthermore, the development of the environmental complex from the 1960s onwards does not follow a linear progression. Instead, it alternates significantly in form and civic attention over time. Uekotter [12] suggests that the shaping of the West German environmental movement resulted from a series of waves spanning from the mid-1950s to the mid-1980s, rather than arising from a single critical turn or awakening.

In this endeavour for a fuller picture than what is typically outlined by ‘environmental historians’ of the Swedish environmental concern in the late 1960s/early1970s, we draw from literature across various disciplines, mainly political science, history of technology, and business history. Additionally, we will incorporate previously unpublished material, including industrial newsletters. Early Swedish environmental policy development has primarily been investigated by political scientists, although briefly also from an historical and partly green nationalism perspective [1,17–19]. Swedish green business and green knowledge production in the 1960s have primarily been studied by historians of technology and business historians, often in collaboration with social scientists [20,21].

Below, we first provide a brief physical geographic background and pollution history for Sweden. Afterward, we embark on our endeavour to draw a fuller picture of Swedish environmental concern in the late 1960s and early 1970s, going beyond the typical narratives presented by traditional environmental historians.

Sweden has 10 million inhabitants (of which 90% live in the southern half of the country), and it is the fifth-largest country in Europe in terms of land area (following Russia, Ukraine, Spain, and France). Hence, Sweden’s population density is quite low. The country’s coastline stretches for 2700 kilometers, contributing to abundant natural and climatic diversity. Additionally, Sweden boasts over 96,000 lakes, teeming with aquatic life. The northern region is characterized by mountains and bogs, while the southern region largely consists of flat farming areas [22].

From a longer-term perspective, Sweden faces several pressing environmental issues.

Acid Rain Damage●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

■

■

■

By way of introduction, we touch upon the first two common focus areas of the traditional historical narrative of Swedish environmental concern in the 1960s. These areas include the increased attention from scientists, experts, and public opinion makers, alongside the growing media coverage of environmental issues.

Subsequently, we aim at broadening the perspective on what environmental concern entailed in Sweden during the late 1960s and early 1970s. We do this by examining environmental policy development and implementation, with a special focus on:

1.

2.

Our exploration concludes with two clarifications:

1.

2.

Finally, the article wraps up with a Concluding Discussion that synthesizes the most important lessons from the broaden perspective of environmental concern in Sweden during the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Science: Establishing Environment and Ecology in Swedish ScienceIn the 1960s, environmental research gained prominence in Sweden. The Swedish Research Council, specifically the Natural Sciences Research Board (NFR, 1946–2000), played a crucial role in establishing the Natural Resource Committee in 1961. Additionally, increased government funding allocated to environmental research contributed significantly to this development [17,26].

The Natural Resource Committee served as a hub for Swedish expertise in nature conservation. Its members advocated for ecology as an independent scientific discipline—a foundation for the rational management of nature. By doing so, the Committee pioneered the integration of ecological principles into academia and society. As intermediaries, the Committee facilitated communication between the NFR, university departments, and individual scientists. They actively identified younger researchers interested in ecological environmental studies. Through negotiations, the Committee initiated several research projects, leading to rapid growth in the funds they administered. By the late 1960s, hundreds of scientists across Sweden’s five universities engaged in scientific activities related to ecology. These activities included announcing undergraduate courses, publishing research reports, and organizing seminars focused on ecological topics [27].

Science: Scientists’ Monopoly on Environmental KnowledgeIn the early stages, Swedish experts and scientists established a monopoly over knowledge creation and dissemination, positioning themselves as the legitimate sources of information. Unlike in other countries, Sweden did not witness significant criticism of science within environmental movements [7,10].

One possible explanation for this phenomenon lies in the robust public support for environmental science and ecology. This strong backing may have contributed to Swedish environmental scientists being less involved in new environmental organizations compared to their counterparts in other nations [7].

Science: The Critical ScientistsAlthough environmental research gained prominence in Swedish science during the 1960s, the process of identifying and characterizing environmental issues as legitimate scientific concerns was not immediate [28]. Critical (natural) scientists in Sweden as well as elsewhere [29,30] therefore published popular science books aiming at increasing the public awareness of the environmental threats. One notable example is the authorship of biochemist Hans Palmstierna.

Interestingly, not all environmental debaters were scientists. Journalists and individuals working within the established political culture also contributed, such as Rolf Edberg, a journalist, member of Parliament, and diplomat. Both Palmstierna and Edberg were active Social Democrats, ideologically influenced by social democratic environmental policy. However, they held contrasting views on environmental problems.

Palmstierna expressed faith in modern technology, scientific research, and the capacity of the political system to address environmental challenges through legislation and planning. His optimism aligned with the traditional social democratic perspective on development and modernization. As a result, Palmstierna had a greater public impact. In contrast, Edberg maintained a more pessimistic outlook. He considered contemporary ecological signs of crisis as evidence of a potentially catastrophic development for human civilization [7,10].

Interestingly, even before the 1960s breakthrough for Swedish environmental debaters, writers like Elin Wägner, poet Harry Martinson, and agricultural chemist Georg Borgström had already published books and articles from an environmentalist perspective. Their contributions predated Rachel Carson’s influential best-seller “Silent Spring” of 1962 [30], which quickly gained attention in Sweden and sparked discussions, including the Swedish mercury debate [8].

Media: Growing Space in Media for Environmental ConcernThe historical research, with a focus on the early Swedish mass media coverage of the environment, mainly discusses how environmental issues gradually gained prominence. While there was a small beginning in the 1950s, it was primarily during the 1960s that these issues found their way into the newsrooms of daily newspapers and television broadcasts. In 1964, Sweden’s first full-time environmental journalist, a woman named Barbro Soller, was hired by Sweden’s largest daily newspaper Dagens Nyheter (DN). Between 1961 and 1969, on the news program Aktuellt on Sweden’s at that time only TV channel, a total of 376 segments (i.e., about one a week), allocated to 141 different reporters’ names, dealt with environmental issues [10].

In the 1950s, there were debates related to nature conservation, particularly concerning water regulation and the preservation of rivers. However, it was in the mid-1960s that the threat of mercury poisoning took center stage and partly paved the way for the environmental debate in Swedish mass media [27].

Media: The Mercury HazardThe press continuously strengthened its agenda-setting function on the mercury issue through close coverage of conferences, symposiums, and scientific reports, presenting mercury as an environmental hazard. Scientists were the actors most often referred to in the press. The reporting favored scientists discussing mercury as an environmental hazard and advocated political action based on scientific recommendations [31].

Some journalists were more engaged in the mercury issue than others. Egan [32] shows how the editorial Carl-Gustav Rosén at the second-largest Swedish daily journal, Svenska Dagbladet, marked the formal creation of an informal and unofficial group of scientists who immersed themselves in the early science and politics of mercury pollution in Sweden. They argued vociferously for a radical response to mercury pollution. The discovery of the environmental threat of mercury resulted from a relatively quick relay of individual discoveries by Swedish researchers, mainly natural scientists, at various government institutions. The fact that the necessary research competence already existed at institutions such as the pioneering environmental research institute IVL (Institute for Water and Air Treatment Research), the Swedish Institute for Public Health, and the Swedish Veterinary Institute was significant for this development [28,33].

Media: The Sulfur Dioxide and Acidification HazardSwedish media also reported on sulfur dioxide emissions and acidification, another pressing environmental hazard in Sweden during the 1960s. Before the acidification discovery, high sulfur concentrations in the air of Stockholm’s inner city and other larger Swedish towns constituted local problems, creating good prerequisites for research and political preparedness on the issue. It all began with a TV feature in December 1966, where the laboratory technician Hans von Ubish at the Swedish Institute for Public Health informed the public of alarming levels of sulfur dioxide in Stockholm’s inner city. This increase was due to newly constructed large apartment buildings heated with oil containing five times more sulfur content than the oil used for smaller buildings. After the TV feature, Valfrid Paulsson, an under-secretary in the Government Offices and future first general director of SEPA (from 1967), contacted Olof Palme, Minister of Infrastructure, and future Prime Minister (from 1969). Six months later, the government decided that all inner-city government properties should be heated with low-sulfur oil. A few years later, Paulsson commented on this quick response, realizing that it was rather easily remedied. Much could be done for the population of Stockholm at a low cost [23,33].

Mass media continued reporting on sulfur dioxide emissions during the summer and fall of 1967, and then expanded the issue to include the large-scale acidification of precipitation and surface water. Key discoveries were made by individual experts and scientists at various government institutions, similar to the mercury and local sulfur dioxide problem. It all started with Ulf Lundin, a fisheries inspector in the local fisheries administration in western Sweden, noticing that the pH value in local lakes had fallen successively. He suspected that the lakes were polluted by acid air pollution from the city of Gothenburg (the second largest in Sweden). Lundin then contacted Svante Odén, acting manager of the Atmospheric Chemistry department at the meteorology department at Stockholm University. Odén was responsible for publishing chemical analyses of precipitation collected over many years from the European atmospheric chemistry network. After reviewing tables, diagrams, and maps, he realized that it concerned large-scale acidification. What he saw was frightening and something that no one had realized before. The public read about the results in Sweden’s largest daily newspaper on October 24, 1967, and the article became a scientific sensation. Within a few days, it had been distributed to newspapers in other European countries and the U.S. [31,33].

The Swedish discovery of acidification in precipitation and water quickly led to a national decision to successively reduce the sulfur content in fuel oil, thereby reducing sulfur dioxide emissions. By the early 1970s, the highest permitted sulfur content of inner-city oil was only 1%. Sweden also began working for international collaboration on the matter. However, it was not until 1985 that 21 European countries ratified the Helsinki Protocol on the Reduction of Sulfur Emissions, aiming to reduce sulfur dioxide emissions by at least 30% from the 1980 level by 1993.

Modern Environmental Policy: The BirthEnvironmental politics, beyond the study of environmental movements and protests, has received inconsistent attention within scholarly research in environmental history [13]. However, social scientists, particularly political scientists, have highlighted the rise of environmental policy, with a strong focus on institutions. Let’s begin with an overview of the elements of early modern environmental policy before delving into the reasons why it was formed as early as it was.

Before 1960, environmental policy and administration in Sweden were characterized by institutional fragmentation and relatively low priority. For instance, the Water Inspectorate, established in 1957, was a small institution tasked with supervising both industrial pollution and reviewing plans for water and sewage system extensions. However, during the early 1960s, several commissions were appointed, and authorities were established with a focus on the environment. These included the Emission Experts in 1963 (to propose an EPACT), the Board for Nature Conservation in 1963, the Air Quality Management Committee in 1964, and the Water Quality Management Committee in 1964. In 1967, the three latter committees were consolidated into SEPA (Swedish Environmental Protection Agency). SEPA not only became the world’s first Environmental Protection Agency (soon followed by counterparts in the U.S. and Japan [34]), but Sweden was also among the first countries to pass comprehensive environmental protection legislation, including the EPACT in 1969. Additionally, Sweden actively supported research programs in environmental science and technology [1,17].

Modern Environmental Policy: SEPA and the Political Process-Tradition of BargainingSEPA’s responsibilities ranged from protecting rare species and managing national parks to developing pollution-control guidelines and administering state subsidies for sewage treatment plants. The work of refining the general principles of the EPACT into more precise admission guidelines and other pollution-reduction criteria led to significant emission reductions from the 1960s to the 1980s, sometimes reaching 90%–95% [21]. An important aspect of SEPA’s approach was following the Swedish tradition of ad hoc investigative commissions preceding administrative reforms and new legislative proposals. Each commission included representatives from various political parties and interest groups in Swedish society. Working groups, comprising industry representatives, environmental authorities, and researchers, effectively addressed pressing environmental problems, and discussed potential solutions for each sector. These working groups further provided SEPA with long-term links with environmental researchers and industry stakeholders [17].

Such bargaining with stakeholders and interest groups, based on a long tradition in the Swedish political process, stood in sharp contrast to the contemporary U.S. political process concerning the environment. In Sweden, the political process emphasized consensus-seeking and pragmatic negotiations, resulting in outcome-oriented policies. Unlike the U.S., where more dramatic processes often led to symbolic goals that existing policy instruments struggled to achieve, Sweden’s approach prioritized practical solutions [1].

Modern Environmental Policy: Not a Prioritization of Ecological ConsiderationsOverall, the implementation of modern Swedish environmental policy did not prioritize ecological considerations. Instead, it adhered to a tradition where environmental quality and nature were just one of many interests, deserving accurate weight in policies and decisions. Even SEPA’s first general director, Valfrid Paulsson, followed this tradition [26,35]. This perspective is also evident in the composition of the Environmental Licensing Board, a special environmental court established in 1969 alongside the EPACT (Environmental Protection Act) to handle applications from polluters seeking permits. The licensing board included an experienced judge as chair, along with three members possessing relevant expertise in environmental, technological, and industrial matters [17].

Modern Environmental Policy: Political Struggles over Hydroelectric Dam ProjectsWhile there was no political struggle over sulfur/acidification or mercury problems in the 1960s, there were disputes related to the exploitation of the Vindel River in northern Sweden by the state-owned energy company Vattenfall. Interestingly, political alignment played a role: the further right politically, the more opposition there was to expansion [36]. In fact, Swedish environmental debaters in the 1960s were surprisingly positive about nuclear energy due to the many struggles over hydroelectric dam projects along the northern Swedish rivers [7]. Another conflict arose in the coastal area of southwest Sweden due to the simultaneous establishment of a large pulp factory and a nuclear power plant near many summer homes. As a response, National Land Use Planning (NLP) was implemented, introducing an ecological perspective to guide overall physical planning [10,37].

Modern Environmental Policy: The Importance of Investigative Commissions and the Welfare StateThe overall strong and early incorporation of environmental concern into the Swedish state apparatus [19] can be understood at several different levels. Of importance was not least the above-described tradition of ad hoc investigative commissions, which already for long had allowed conservation interest to be represented when issues involving nature/natural resources were investigated. Hence, Swedish economy is built on access to minerals and timber (and previously also fisheries), which early on there was reason to manage efficiently. Thus, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, several state agencies were implemented and charged with conservation (e.g., Sveriges geologiska undersökning, 1858, for geology; Domänverket, 1859, for forest management; Fiskeristyrelsen, 1948, for fisheries).

At a general level, it was also important that Sweden was in the midst of a successful welfare state building. From upholding a constructive state-administered capitalism with a clear separation of the public and private sectors—the productive capacity primarily in private hands, and the state administering the reproductive spheres of education, health care, research, etc.—post-war Sweden managed to combine high per capita living standards with high-quality social welfare. The political and economic development benefited from Sweden being spared from the destruction affecting most other European countries during the Second World War. Also, the Social Democratic Party was able to retain power for 44 years (1932 to 1976), thereby providing political stability alongside a fair amount of administrative self-confidence and authority.

Building on the effective utilization of modern science-based technologies, the Swedish welfare state was busily constructed in the 1960s [38]. Ambitious programs included social housing projects, highways, waterpower plants, sewage treatment facilities, as well as social insurance systems and active labor-market policies [7,39]. As the negative side-effects of societal development, such as pollution and environmental damage, became increasingly tangible, the Swedish government took on the task of solving these problems with the same science-based and development-optimistic spirit as in previous programs. Additionally, there was a belief, fostered through continuous dialogue in Swedish official debates from the 1930s to the 1970s, that it would be possible to harmonize society and nature, thereby enhancing human welfare [18].

The State/Industry Consensus RelationshipOf importance in the Swedish context was further an overall effective consensus relationship between the Swedish government and industry. The lion’s share of society’s knowledge about environmental problems and their remedies in the 1960s and early 1970s was developed in close understanding and cooperation with business. Viewed from a solution-oriented perspective, this was not surprising given that the fight against pollution defined Swedish environmental concern early on, and business/industry accounted for a major part of it. Also, regulating industrial pollution is very much about creating the preconditions (knowledge and technology) for reducing emissions. The Swedish case of close collaboration between controller and polluter is to be understood also from the perspective of the outcome-oriented political process and the tradition of ad hoc investigative commissions described above.

In line with the special style of Swedish environmental policy, the first director general of SEPA, Valfrid Paulsson, argued for a relationship between regulators and polluters characterized by prudence and reason. He saw information as a major vehicle; if each side knew exactly what the other wanted and why, this would lead to rational and balanced decisions. Another keyword was trust; polluters should be relied upon to implement any agreed-upon pollution-control programs and prescribed control-measurements without day-to-day interference from the regional and/or local environmental officers [17]. During an official appearance after SEPA had been in operation for four years, Paulsson maintained that the ‘trustful’ cooperation between the business community, science, and authorities was decisive for SEPA’s possibility to establish guidelines for the environmental protection process. He was convinced this had saved many years of environmental protection work for Sweden [40].

The State/Industry Consensus Relationship: The Importance of IVL Part 1The pioneering environmental research institute IVL (Institute for Water and Air Treatment Research), co-funded (50/50) by industry and government, played a major role in creating the preconditions for reducing emissions. The institute was established on the initiative of the Federation of Swedish Industry (representing all major industry sectors in Sweden) and started operations in January 1966. The focus of IVL was green knowledge and technology development, with industry as an essential collaborative partner [41].

There were extensive win-win possibilities for industry and government. The government needed mobilizing knowledge in the environmental field (in the early 1960s, there was still very little environmental/ecological research at the universities to speak of). Not least, in the specific case of industrial pollution, which was the target of the EPACT, industry had much to gain by sharing the ever-increasing costs of green knowledge production with the government. Moreover, industry considered it important to allow the government a complete view of its actual prerequisites on the pollution side to avoid unrealistic requirements from the environmental authorities [41].

A service company, IVL AB, wholly owned by industry, was formed in connection to IVL. IVL and IVL AB worked closely together; the service company personnel brought problem formulations to the institute, which developed solutions that, in turn, could be quickly tested or implemented in existing industry (through the service company). The Board of IVL, where SEPA, industry, and researchers from IVL were represented, established the main direction of the research operation through multi-year plans. The early operations involved the development of methods, standards, and devices to measure and assess the character, extent, and impacts of industrial emissions. The activities furthermore entailed restoring the receiving water body and developing and installing methods for the treatment of industrial waste, especially wastewater. The importance alone of the development of measurement standards and devices—to be able to measure the scale, impact, and remediation of emissions—cannot be overemphasized [41,42].

The number of commissions of both IVL and IVL AB quickly grew to an extent that could not have been foreseen at the time of its founding, i.e., by an average rate of 30% and 45% annually in the late 1960s/early 1970s. The growth reflects the gap in Swedish specialist knowledge on industrial pollution, a gap that IVL had been created to fill. At the time, IVL was the only solid organization in Sweden with the requisite knowledge and research capabilities to operate within the environmental field, thus becoming a central resource for Swedish authorities to consult on a wide range of environmental issues. It further reflects a great demand from industry and the joint mobilization of industry and authorities to measure the scale and impact of emissions. The strong agreement between the government and industry on the value of IVL in turn conferred legitimacy on the knowledge and technology developed there. Apart from developing methods for measuring the scale and impact (and remedy) of industrial emissions, IVL worked more broadly as a mediator of environmental knowledge in the public sphere. This is partly reflected in the research it conducted on the environmental effects of sulfur dioxide and the consumption of petroleum and detergents. In some cases, IVL also worked as an international environmental expert and was repeatedly hired by the WHO and UNESCO in the late 1960s and onwards for matters concerning the analysis and remediation of oil spills and mercury pollution [41].

The State/Industry Consensus Relationship: The Importance of a Proactive Business CommunityThe model for IVL AB had already been applied in the Swedish pulp and paper (P&P) industry for some years. The widespread and polluting P&P sector had long been the lead industrial sector in organizing R&D on air and water pollution. Due to local pollution opinions, it appointed a committee already in 1908 to investigate methods to reduce the odour problems of the sulfate pulp industry. The so-called Water Pollution Committee followed in 1940, and it was further developed into the Water Laboratory of the Forest Industry in the mid-1950s. Central explanatory factors behind this organization were both a continuously strengthened health- and water legislation over time, and the sector’s ambition to solve the pollution problems with internal processes rather than end-of-pipe solutions (hence, emissions are equal to waste of resources), and internal process solutions obviously require more R&D [42].

The strengthened health- and water legislation affected other industrial sectors too, and this justified the Federation in establishing a common service platform in the 1950s. Several industrial leaders were motivated to cooperate in counteracting pollution problems also since pollution bothered employees and management locally. The sharing of pollution-related knowledge among one another was overall considered beneficial in Sweden at the time [42].

The State/Industry Consensus Relationship: The Importance of IVL Part 2As noted above, the mercury issue became a catalyst for the environmental debate in Sweden, and here IVL contributed with both central discoveries for understanding the formation of toxic methylmercury and developed methods for handling mercury-contaminated sediments. In this connection, the IVL researcher Arne Jernelöv contributed to the discovery that all organic mercury that ended up in the sea by way of the air was transformed into toxic methylmercury in the bottom sediment [28,43]. This important discovery and the development of methods to handle contaminated sediment contributed to Jernelöv and others from IVL assisting in the aftermath of the Japanese Minamata disaster in 1968 [41,43].

In 1966, when Jernelöv, a young man with a novel background in ecology, applied for and was called for an interview for a research position at the newly established IVL, he was surprised to hear that the institute was a government/industry joint initiative. He expressed great doubts; he did not see industry as a constructive force in the context of air and water pollution and declared he was no longer interested in the position. IVL’s CEO, Stig Freyschuss, however, was assertive. He wanted to hire Jernelöv and maintained that he could expect positive surprises, as several industry leaders truly understood that they had problems and wanted to remedy them. Freyschuss understood that IVL needed Jernelöv to incorporate the most novel ecological competence to match the needs in industry and society at large.

Animals and nature had been Jernelöv’s major interest for as long as he could remember. When in university in the early 1960s, there were not yet any courses in environment/ecology, but he put together courses that dealt with pollution issues, such as limnology and marine biology, in his degree. When Jernelöv later was offered the position, he declared he was willing to accept it if he were free to start his own projects alongside the work already being conducted at IVL. Freyschuss granted him considerable freedom and (according to Jernelöv) kept the promise. In retrospect, Jernelöv states that IVL was the perfect workplace, both because the mandate was broad and because the institute had unique access to industry and, not least, good financial resources and great freedom to use these effectively [44].

What made IVL truly unique was the way in which the institute, along with the service company, worked with the whole spectrum of environmental problems, from identifying them in industry and the rest of society—in waterways and in the air—to solving them with environmental technology. IVL managers from the 1960s up until the 1980s repeatedly pointed out that if you have the whole picture of a problem, you solve it differently than if you are only looking at a small part of it. In combination with the new environmental legislation and extensive government subsidies to industry for environmental technology, IVL contributed extensively to the far-reaching emissions reductions in Swedish industry in the 1960s and 70s [41]. The U.S. Representative and chairman of the House Subcommittee on Conservation and Natural Resources, Henry S. Reuss, visited Sweden in late spring of 1970 (possibly related to the upcoming UN conference). He later reported on the visit in an article in the Columbia Journal of World Business. Reuss was impressed by the cooperation between industry and the government and found ‘the atmosphere of cooperation within IVL’ especially impressive. Swedish industry, he noted, ‘far from waiting to be nudged by the government takes frequent initiative and presses the government to environmental action’ [45].

Lack of a Significant Popular Environmental MovementWhat we said above about reactions in the media and among individual scientists, as well as about the progressive policy development (similar to the German case [46,47]) and government/industry consensus and pioneering research institutes, were all these important initiatives undertaken in the absence of a significant popular/grassroots movement. This fact has not really engaged scholars but is nonetheless an important piece of the puzzle of Swedish environmental concern in the late 1960s and early 1970s. A bit carelessly, a ‘membership increase’ in the Society for Nature Conservation has by some scholars been taken as an indicator that there was some form of popular movement in the 1960s after all [48–50].

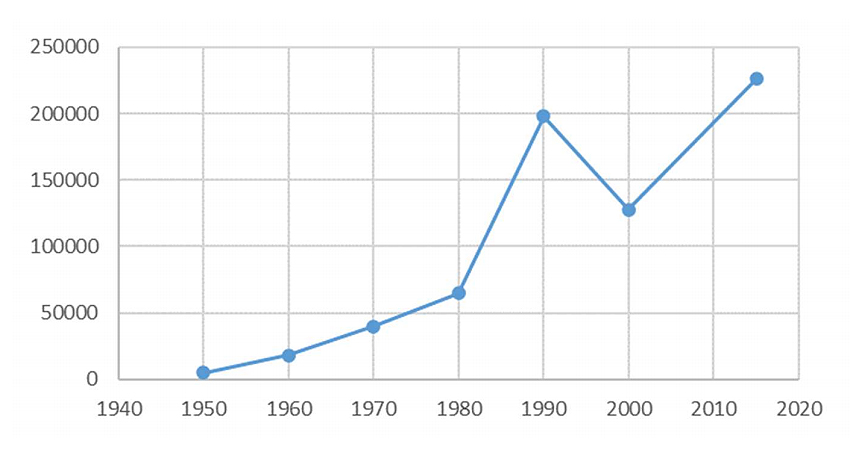

In reality, this did not concern a markedly increased membership during either the 1950s, 1960s, or the 1970s; membership increase was gradual but rather modest during all three decades (see Figure 1). It is further overall skewed to refer to a growing number of members in the Society as an indicator of a popular environmental movement in the 1960s, given that the organization at that time (although the ambition was to be a popular organization) was rather an expert organization with relatively close relations to the state. The strengths with which environmental concern was incorporated into the Swedish state apparatus have, in fact, been suggested as a handicap for environmental concern in carving out a public space of its own [7,17].

A true breakthrough in membership in the Society for Nature Conservation did not take place until the 1980s (see Figure 1). Then several key environmental events took place that help explain both the increase in membership and the fact that the environment captured the attention of Swedish citizens, as reflected in voter surveys conducted before every parliamentary election. This was particularly evident before the 1988 election when the Green Party first entered the Swedish parliament. In only a few years in the mid-1980s, Swedish citizens were shaken by both the Chernobyl accident, a significant and sudden decline in the seal population (which would later turn out to be a virus outbreak), and the dioxin alarm (it became known that highly toxic, carcinogenic dioxins were formed in the production of bleached pulp, an important Swedish export product) [15].

Figure 1. The Development of Members in the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation, 1950–2015. Source: based on data retrieved from www.snf.se.

Figure 1. The Development of Members in the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation, 1950–2015. Source: based on data retrieved from www.snf.se.

In the voter surveys prior to the 1964 and 1968 national elections, on the other hand, environmental concern was overall weak among the broader segments of Swedish society. Prior to the 1964 election, not a single voter in the survey mentioned (in open questions) the ‘environment’ or ‘nature conservation’ as important. Prior to the 1968 election, although the problems with mercury poisoning and sulfur emissions were still being debated in the Swedish press, only four percent did so [50].

The lack of—likewise the opportunity to create—a general opinion on the elevated sulfur dioxide levels was raised by physicians in the Swedish Medical Journal (Läkartidningen) on September 13, 1967 (referenced in DN the following day):

‘It is possible that a strong public opinion must be awakened in order to force authorities, industry, and individuals into faster and more effective measures than the ones that have been undertaken so far. It is greatly in the medical corps’ interest not only to support but also actively contribute to such opinion formation’ [51].

The UN Conference on the Human EnvironmentIn the context of the proactive Swedish government in terms of both policymaking and implementation, it is natural to assume, as Jamison et al. (1990) have done, that the fact the first UN Conference on the Environment (The UN Conference on the Human Environment) was held in Stockholm in 1972 can be traced back to an ambition of the Swedish government to present itself as an international leader in environmental concerns. However, it started as an independent move by the Swedish UN delegation in the fall of 1967 [52].

The Swedish UN delegate, Sverker Åström, discusses this in a biography published in Swedish (1992) [53]. The initiative of the delegation was influenced by Swedish opinion makers (including Palmstierna), researchers, and some politicians (including Palme) who warned and informed about environmental disturbances during this period. Additionally, favourable conditions within the UN administration contributed to this initiative. Inga Thorsson, a Swede in the UN Secretariat in New York, informed the Swedish delegation that the UN Committee for Science and Technology had proposed another conference (the fourth in order) about the use of nuclear energy. However, Thorsson and the Swedish delegation believed that sufficient expensive UN conferences about nuclear energy had already been held, suspecting they were intended to serve Western-world interests, especially American industry.

Without instructions from Stockholm, the delegation decided on December 13, 1967, before the General Assembly’s discussion of the Committee for Science and Technology’s proposal, to suggest that states consider a major UN conference in the early 1970s with the general purpose of promoting cooperation between countries on environmental protection and raising awareness of the seriousness of the problem. It wasn’t until a few months later (in the spring of 1968) that the delegation proposed to the Swedish government to take formal initiative in this matter. In the fall of 1968, the General Assembly unanimously adopted the resolution submitted by the Swedish delegation, and a preparatory committee was appointed, with Sweden as an obvious member. Finally, in the fall of 1969, it was decided that the conference would take place in Stockholm in 1972 [53].

Åström notes that until the fall of 1969, practically all decisions were adopted unanimously. This was partly because the topic was considered ‘new and stimulating’ and ‘in fashion.’ Additionally, Sweden’s reputation as a ‘decent, progressive, and neutral’ state that was not ‘suspected of running errands for any major power’ played a role. The UN Secretariat, according to Åström, was ill-equipped for the environmental debate. Philippe de Seynes, Under-Secretary-General for Economic and Social Affairs, sought advice and help from the Swedish delegation. The delegation took primary responsibility for the issue, authoring the draft for the first circular letter on the matter and coordinating national reports from all member countries. Seynes also commissioned Åström to convince Canadian oil and mineral businessman Maurice Strong to become the general secretary for the conference [53].

During the preparations for the conference, it gradually became obvious to Swedish businesses that the mutual understanding and close cooperation between Swedish business and governing authorities in environmental issues would not be relevant to the conference. This was frustrating for the Federation of Swedish Industry and likely also for the IVL-organisation, and large parts of the Swedish business community. At this stage, they had managed to achieve extensive environmental knowledge development and emissions reductions through close collaboration with Swedish authorities.

As a result, the Federation of Swedish Industry, in cooperation with the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), took the initiative to arrange their own World Industry Conference on the Human Environment. This conference was held in Gothenburg in May 1972, a couple of weeks before the UN Conference in Stockholm later that June. Even before this, Swedish industry had organized international conferences related to the environment, such as the first International Congress on Industrial Wastewater in Stockholm from November 2–6, 1970. Despite the short preparation time for the conference in Gothenburg, 100 delegates from 14 countries attended. Notably, Japan was the only major industrial country absent [54,55].

The organizers’ intention with the conference was to clarify the international business community’s view of environmental issues and demonstrate their participation, both then and in the future, in international environmental cooperation. During the conference, a letter was written with the combined viewpoints of the international business community. This letter was later distributed to all delegates at the UN conference. Among other things, the letter proposed that businesses considered themselves able to contribute to a better environment and were determined to play an active and constructive role in environmental work in collaboration with authorities [55].

Despite being sidelined in relation to the 1972 UN conference, business and the ICC gradually established themselves as key partners to the UN. Their emphasis on economic growth, market forces, and business self-regulation became increasingly important in international environmental governance over the coming decades. Unfortunately, this has not reflected the real need for measures to prevent the ongoing environmental crisis [16].

The most important lessons from the broadened perspective of environmental concern in Sweden during the late 1960s and early 1970s are that it has taught us to reconsider it as something that could grow within business, industry, and government authorities, in parallel (and sometimes prior) to public opinion and opinion makers advocating for the environment.

The broadened perspective also prompts us to question whether it concerned an awakening. There was significant readiness within several Swedish government institutions, including IVL (Institute for Water and Air Treatment Research), to increasingly discover, understand, and address the growing environmental problems. By the mid-1960s, individuals such as experts, civil servants, and politicians were taking early and important initiatives on behalf of the environment. They often went beyond their professional expectations, but they had the mandate to make significant contributions.

Hence, the dissonance between humanity and nature, as well as the interest in managing natural resources, was not entirely novel. Industrial pollution had already been partially regulated, albeit in a fragmented manner, several decades before the 1960s. The background for the industry’s proposal of cooperation with IVL in the mid-1960s lies here. IVL was established in 1966 and played a crucial role in filling the knowledge gap related to environmental issues, considering the whole picture of the problems. This occurred even before the establishment of the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA) in 1967, the Environmental Protection Act (EPACT) in 1969, and the development of environmental research at Swedish universities.

In terms of policy relevance, it is worth emphasizing how the Swedish environmental concern during the late 1960s and early 1970s focused on green business and knowledge-based policy implementation. In part, the tradition of consensus-seeking and pragmatic negotiations still prevails in the Swedish policy process, resulting in outcome-oriented policies, see e.g., [56]. This approach has likely contributed to the Swedish progress during the last three decades in terms of reducing greenhouse gas emissions while maintaining a thriving economy. However, the previous collective effort to address industrial emissions has shifted. Instead of sector-wide initiatives, individual companies (and sometimes sector associations) now play a key role in developing green technology and know-how. These efforts are often partially supported by the government, e.g., such as through the co-funding of industrial pilot plants. The Institute for Applied Environmental Research (IVL), which had its heydays in the 1960s up until the 1980s, has seen its influence decline over time. Initially, addressing environmental challenges involved targeting low-hanging fruits—i.e., relatively straightforward and low-cost solutions. For instance, the development of measurement standards and devices significantly benefited various industry sectors. However, as we face more complex industrial pollution issues today, technical solutions require greater sophistication, and more radical system change.

All data generated from the study are available in the manuscript.

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

Söderholm K. Green Business and Knowledge-Based Policy Implementation in Sweden in the 1960s and 1970s. J Sustain Res. 2024;6(3):e240039. https://doi.org/10.20900/jsr20240039

Copyright © 2024 Hapres Co., Ltd. Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions