Location: Home >> Detail

TOTAL VIEWS

J Psychiatry Brain Sci. 2025;10(6):e250020. https://doi.org/10.20900/jpbs.20250020

1 Department of Computer Science, Kent State University, Kent, OH 44224, USA

2 Department of Psychological Sciences, Kent State University, Kent, OH 44224, USA

* Correspondence: Jianfeng Zhu

Large language models (LLMs) have transformed natural language processing, enabling contextually coherent text generation at scale. Although conversational language contains signals associated with personality traits, mapping naturalistic conversation to stable personality-related representations remains challenging.

We introduce a real-world benchmark for personality-related inference in LLMs, using 555 semi-structured interviews paired with BFI-10 self-report measures as reference labels. Four recent instruction-tuned models (GPT5-Mini, GPT-4.1-Mini, Meta-LLaMA, and DeepSeek) are evaluated under zero-shot and chain-of-thought (CoT) prompting, predicting individual BFI-10 items and aggregated Big Five trait scores on a 1–5 Likert scale.

Across models, repeated inference runs exhibited high internal consistency under fixed settings, but alignment with self-reported personality was weak, with low correlations (r ≤ 0.27), minimal categorical agreement (Cohen’s κ < 0.11), and systematic overestimation toward moderate-to-high trait values. CoT prompting and extended input context provided limited benefits, yielding modest improvements in trait distribution alignment for some models without consistently improving trait-level accuracy or cross-model agreement.

Overall, this benchmark characterizes how LLMs map state-rich conversational language to personality-related inferences under constrained observational settings, highlighting current limitations and informing future work on personalization and user-adaptive conversational systems.

Personality refers to enduring individual differences in characteristic patterns of thinking, feeling and behaving [1]. These differences encompass emotional tendencies, motivations, and values that influence health, well-being, and interpersonal functioning. Understanding personality-related variation has broad relevance across domains such as psychological diagnosis and regulation [2,3], criminal justice [4,5], affective computing [6,7], and personalized AI systems [8–10]. Among existing frameworks, the Five Factor Model (FFM) [11] is one of the most widely adopted, defining five broad dimensions: Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, and Openness [12]. Extensive research has shown that these dimensions are associated with important life outcomes, including interpersonal behavior, emotional experiences, work performance, and vulnerability to mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety [13,14].

Early computational approaches to personality inference focused on digital footprints, notably Facebook likes, to predict personality traits [15,16]. While initially promising, these methods faced significant ethical and privacy concerns, exemplified by the Cambridge Analytica scandal. More recent research has shifted toward publicly available textual data, such as social media posts, using natural language processing and machine learning techniques to infer personality-related characteristics [17]. Despite methodological advances, many existing studies rely on synthetic or social media–derived datasets labeled through crowdsourcing or simplistic binary annotations, limiting their ecological validity and raising questions about their generalizability to real-world contexts [18]. Traditional psychological methods for measuring personality primarily depend on self-report questionnaires, which, although validated, can be time-consuming and resource-intensive, limiting scalability in large or interactive applications [19,20].

The emergence of LLMs, such as OpenAI’s GPT and Meta’s LLaMA, has introduced new opportunities for modeling psychologically relevant information from language. These models provide a wide range of capabilities, including functioning as conversation agents, generating essays and stories, writing code, and assisting in diagnostic reasoning [21–25]. As a result, researchers have begun exploring their potential for personality-related annotation and inference from text [26,27]. However, a critical question remains: to what extent can LLMs extract personality-related signals from real-world conversational language under realistic observational constraints?

To address this question, we benchmark four state-of-the-art LLMs (GPT5-Mini, GPT-4.1-Mini, Meta-LLaMA, and DeepSeek) on their ability to infer Big Five personality traits from a novel, ecologically valid dataset. We analyze 555 semi-structured interviews designed to elicit autobiographical reflections on recent emotional and social experiences, collected concurrently with validated Big Five Inventory (BFI-10) self-report scores [28,29]. This specific interview paradigm has already demonstrated predictive utility in eliciting responses broadly predictive of psychological processes and adjustment (e.g., risk of mental health conditions, social functioning, the role of prior experiences in adaptation etc) across a range of contexts (e.g., post trauma, during chronic stress, during developmental transitions [30,31]).

We conduct a systematic evaluation of model outputs under different inference conditions, examining alignment with self-report personality measures as well as the stability and consistency of predictions across repeated runs and varying input context lengths (Figure 1).

This study investigates the following research questions:

RQ1. To what extent can LLMs perform personality inference from naturalistic, semi-structured interview transcripts?

RQ2. Does CoT prompting improve alignment between LLM-based personality inference and self-report personality measures compared to zero-shot prompting?

RQ3. How well do the distributions of LLM-based personality inferences align with binned self-report distributions?

RQ4. How consistent are personality inferences generated by LLMs across repeated runs, across different models, and under varying input context lengths?

By answering these questions, we aim to characterize the capabilities and limitations of contemporary LLMs in modeling personality-related information from conversational language and to inform the development of personalized and user-adaptive AI systems grounded ecologically valid data.

We utilized a novel dataset comprising 555 U.S. adults recruited across multiple behavioral research studies focused on adjustment to adverse or transitional life events (e.g., occupational stress, health conditions). All participants provided written informed consent and participated in interviews that were audio recorded for later transcription. Interviewers followed a script that included standardized prompts already demonstrated to elicit responses that broadly can predict psychological processes and functioning [31,32]. The full set of interview questions and example response excerpts are provided in Supplementary Materials Tables S1 and S2.

The sample was demographically diverse and balanced by sex (275 male, 278 female; sex missing for n = 2), with participants ranging widely in age (M = 39.4, SD = 16.33), racial backgrounds (431 White, 122 non-White/Other), and education levels (from high school to college and above). A representative sample of participant responses across the five core questions is provided in Table 1.

Interview transcripts were preprocessed using a standard natural language processing pipeline. Text was lowercased, punctuation was removed, English stopwords were filtered using the NLTK library, and repeated words or filler phrases were truncated. Following preprocessing, 518 participants with complete and valid BFI-10 scores were retained for analysis. The BFI-10 was administered during the same session as the interview, providing self-report reference scores on a 1–5 Likert scale [33] for the five personality traits: Conscientiousness, Agreeableness, Neuroticism, Openness, and Extraversion.

LLMs and Prompting StrategiesTo assess LLM-based personality inference, we benchmarked four recent instruction-tuned models:

GPT-4.1-Mini/GPT-5-Mini (OpenAI, 2025): A lightweight, high-performance proprietary model accessed via the OpenAI API, optimized for efficient inference while maintaining competitive reasoning and language-understanding capabilities [34].

Meta-LLaMA-3.3-70B-Instruct-Turbo: A 70B-parameter instruction-tuned model, designed for alignment with human instruction following [35].

DeepSeek-R1-Distill-70B: A distilled variant emphasizing low-resource deployment while maintaining core language modeling abilities [36].

For models that exposed decoding controls, we used a fixed low-temperature setting (temperature = 0.2). For GPT-5-Mini model, temperature was not user-configurable via the API and default decoding behavior was used. No explicit top-p/top-k constraints were set. All inference settings were held constant within each model across runs.

Zero-Shot PromptingZero-shot prompting requires the model to perform the task using only a natural language instruction, without any demonstrations or examples. This setting is conceptually simple, avoids reliance on potentially spurious correlations introduced by in-context examples, and represents a strong baseline for evaluating inference capabilities [37].

CoT PromptingCoT prompting elicits explicit intermediate reasoning steps prior to the final answer. CoT facilitates multi-step decomposition of complex problems, increases interpretability by exposing the model’s reasoning path, and has been shown to improve performance on tasks requiring mathematical reasoning, commonsense inference, or symbolic manipulation [38].

For BFI-10 prediction, a zero-shot prompting strategy was used: models received the participant’s response and were asked to generate ten item-level BFI scores (1–5 scale) without examples or reasoning scaffolds. This tested the LLMs’ capacity to infer personality-related signals from naturalistic language.

For Big Five inference, we compared zero-shot and CoT prompting. In the zero-shot condition, models generated direct 1–5 trait-level scores for the five dimensions. In the CoT condition, prompts guided models through multi-step reasoning: identifying relevant linguistic cues, reflecting on their implications, and synthesizing a final trait score. The prompt templates are provided in Supplementary Materials Boxes S1 and S2. This design tested whether structured reasoning enhanced inference quality relative to the baseline.

Evaluation MetricsModel predictions were evaluated using a comprehensive evaluation framework that captures accuracy, consistency, and interpretability across continuous and categorical scoring formats.

Criterion Validity: Pearson correlation coefficients along with corresponding 95% confidence intervals and Spearman ρ values, quantified the relationship between predicted and self-reported personality scores. These metrics were applied to both BFI-10 item predictions and Big Five trait estimates under both prompting conditions.

Prediction Error: Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) captured average and variance-weighted deviations, respectively. MAE reflects the average magnitude of error regardless of direction, while RMSE provides a variance-weighted indicator that penalizes larger deviations.

Categorical Alignment: For self-reported BFI-10 data, we applied standard binning conventions from prior literature: Low (1–2), Moderate (3), and High (4–5). Since LLM-predicted scores are continuous, we discretized them using a coarser scheme: Low (1.0–2.49), Moderate (2.50–3.49), and High (3.50–5.0), to enable bin-wise comparison. From this, we computed (1) exact match rate (i.e., proportion of predictions falling into the same bin as the self-report reference), (2) off-by-one accuracy (i.e., within one adjacent bin), and (3) Cohen’s kappa (κ), a chance-adjusted agreement statistic.

Model Consistency and Inter-Model Agreement: We conducted two complementary analyses to evaluate the consistency of LLM-based personality inference: (1) inference stability within a single model across repeated runs, and (2) agreement across different models for the same individuals.

Inference stability was assessed using GPT-4.1-Mini on a randomly selected subsample of 50 participants. Model inference was repeated three times using identical interview transcripts, with minor perturbations introduced by randomizing the order of input segments.

Inter-model agreement was evaluated by comparing personality trait predictions generated by different models (GPT-4.1-Mini, DeepSeek, Meta-LLaMA) for the same participants. Treating models as raters and participants as targets, we quantified agreement across models using correlation-based measures and intraclass correlation coefficients.

Ablation Analysis: Input LengthTo evaluate how input context length influences performance, we conducted an ablation analysis using GPT-4.1-Mini across three levels of transcript truncation. Specifically, we compared predictions generated from transcripts truncated to the first 100 words (response_short), the first 1000 words (response_medium), and the full-length interview (response_full). The average full transcript length was approximately 2955 words (SD = 1855). This analysis allowed us to assess how contextual richness affects the accuracy, consistency, and categorical alignment of Big Five trait predictions. We observed statistically significant effects of input length on predicted trait values for all five Big Five dimensions, all p < 0.001: Conscientiousness (χ² = 86.71), Agreeableness (χ² = 288.19), Neuroticism (χ² = 177.63), Openness (χ² = 466.25), and Extraversion (χ² = 175.89).

Model outputs were evaluated using continuous and categorical metrics based on binning. Predicted scores were converted to ordinal categories (Low, Moderate, High) to examine trait-level alignment across input lengths.

Figure 2 and Table 2 summarize model performance across the ten BFI-10 items using Pearson correlation, MAE, and RMSE. Overall, correlations were low for all models and traits, ranging from −0.18 to 0.27, indicating limited alignment between text-derived predictions and self-reported item scores. Relatively higher correlations emerged for BFI-2 (“is generally trusting”), BFI-3 (“tends to be lazy”), BFI-7 (“tends to find fault with others”), and BFI-10 (“has an active imagination”). By contrast, BFI-5 (“has few artistic interests”) and BFI-6 (“is outgoing, sociable”) yielded negative correlations across all models. Among the models, GPT-4.1-Mini showed the strongest but still weak associations, peaking at r = 0.27 for BFI_3. The lowest correlation was observed for Meta_LLaMA on BFI-5 (r = −0.18).

Error-based metrics revealed substantial deviations between predicted and true item scores. Meta_LLaMA produced the highest MAE and RMSE values, with mean errors approaching 2.0 across items. Its poorest performance occurred on BFI_3 (MAE = 2.6; RMSE = 2.9) and BFI-1 (MAE = 2.1; RMSE = 2.5), followed closely by GPT5-Mini. DeepSeek, despite showing the near-zero or negative correlations, achieved the lowest MAE and RMSE score on several items (BFI-2 and BFI-7 to BFI-9), with values around MAE ≈ 1.2 and RMSE ≈ 1.5. Table 2 summarizes these best and worst performing cases and notes interpretability considerations.

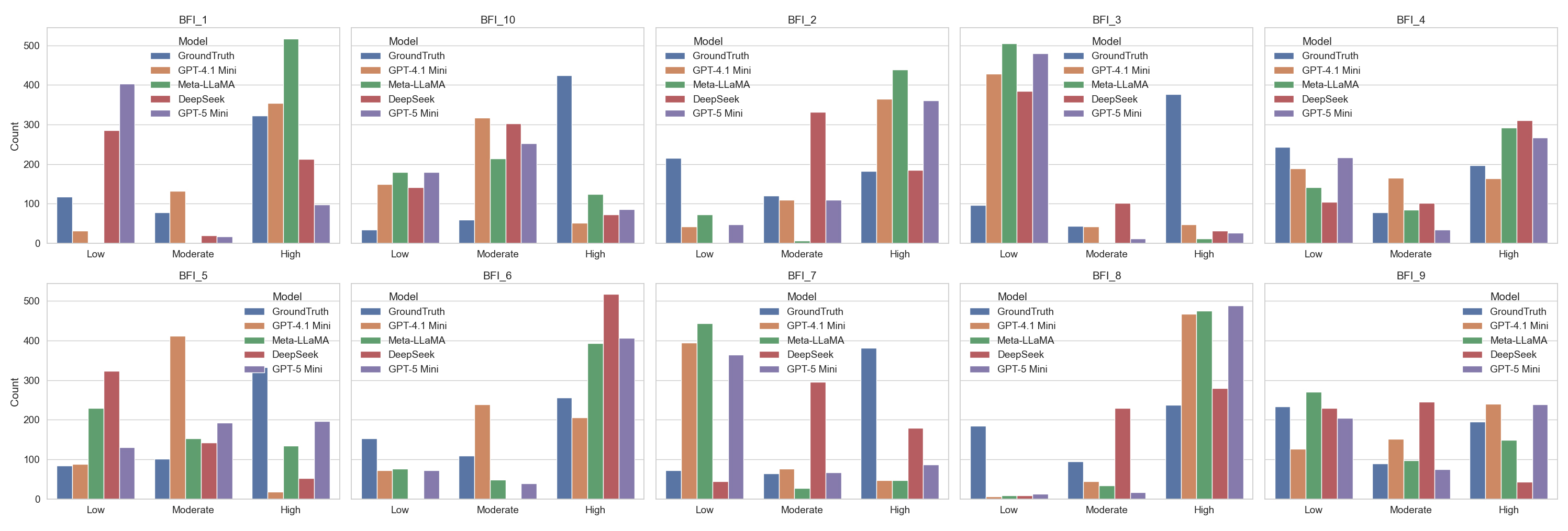

Figure 3 visualizes predicted response distributions on the 1–5 scale relative to empirical human response frequencies. Discrepancies were most pronounced for BFI-3, BFI-5, BFI-7, and BFI-10, where prediction errors exceeded 200 responses in some bins. For instance, on BFI-10 (“has an active imagination”), the self-report reference frequency for high scores (4–5) was approximately 400, where GPT-4.1-Mini and DeepSeek predicted fewer than 100. More consistent alignment was observed for BFI-4 (“is relaxed, handles stress well”) and BFI-9 (“gets nervous easily”), with GPT5-Mini showing the closest match. Across multiple items, including BFI-1, BFI-2, BFI-3, BFI-7, and BFI-8, models performed poorly in the low-score bins, frequently underestimating counts by approximately 200.

Figure 3. Binned distributions of BFI-10 responses: Self-report reference vs. model predictions. (Each panel represents one BFI-10 item, with bar heights indicating the number of responses in each Likert bin ([1–2.49], [2.5–3.49], [3.5–5]) across self-report reference data and predictions from models Compared to human responses, LLMs tend to underutilize the neutral category and over polarize predictions toward the extremes.)

Figure 3. Binned distributions of BFI-10 responses: Self-report reference vs. model predictions. (Each panel represents one BFI-10 item, with bar heights indicating the number of responses in each Likert bin ([1–2.49], [2.5–3.49], [3.5–5]) across self-report reference data and predictions from models Compared to human responses, LLMs tend to underutilize the neutral category and over polarize predictions toward the extremes.)

Figure 4 reports the exact match rates, off-by-one accuracy, and Cohen’s kappa values. Exact match rates ranged from 18% to 63%, with Meta-LLaMA achieving the highest exact match on BFI-1 (“is reserved”, 62%), and GPT-4.1-Mini the lowest match rate on BFI-10 (“has an active imagination”, 18%). Off-by-one accuracy was substantially higher, with most values exceeding 70%; GPT-4.1-Mini reached 88% for BFI_5, and DeepSeek achieved 88% for BFI_7. The lowest off-by-one accuracy was observed for Meta_LLaMA on BFI_3 (29%), followed by DeepSeek on BFI_7 (39%). Despite these moderate accuracy levels, Cohen’s kappa scores remained uniformly low, often near zero or negative (e.g., BFI-5 and BFI-6), indicating that much of the agreement was driven by chance rather than genuine predictive alignment. For completeness, we report both Pearson r and Spearman ρ correlations, along with 95% confidence intervals, in Supplementary Material Table S3.

Figure 4. Exact match rate, off-by-one accuracy, and Cohen’s kappa across BFI-10 items and models. (This figure presents three agreement-based evaluation metrics across BFI-10 items for each model: Exact Match Rate (top), Off-by-One Rate (middle), and Cohen’s Kappa (bottom). While Off-by-One accuracy is relatively high across all models, Cohen’s Kappa reveals stronger item-level agreement for GPT-4.1-Mini, especially on BFI_3 and BFI_7. Meta-LLaMA shows moderate consistency, while DeepSeek demonstrates lower exact match and kappa agreement, suggesting less alignment with human-rated personality scores.)

Figure 4. Exact match rate, off-by-one accuracy, and Cohen’s kappa across BFI-10 items and models. (This figure presents three agreement-based evaluation metrics across BFI-10 items for each model: Exact Match Rate (top), Off-by-One Rate (middle), and Cohen’s Kappa (bottom). While Off-by-One accuracy is relatively high across all models, Cohen’s Kappa reveals stronger item-level agreement for GPT-4.1-Mini, especially on BFI_3 and BFI_7. Meta-LLaMA shows moderate consistency, while DeepSeek demonstrates lower exact match and kappa agreement, suggesting less alignment with human-rated personality scores.)

Figure 5 presents zero-shot and CoT model performance on the aggregated Big Five traits. Across all traits and prompting conditions, correlation remained weak (r < 0.30). Conscientiousness produced the highest correlation across models, with GPT-4.1-Mini achieving the best performance under zero-shot prompting (r = 0.25). Meta_LLaMA showed the weakest overall performance, with negative correlations for Extraversion and Neuroticism in the zero-shot prompting, and uniformly negative or near-zero correlations CoT prompting.

Error-based metrics (MAE, RMSE) were generally above 1.0 for all traits except Openness. Agreeableness consistently exhibited the highest error rates across all models and prompting types, while Openness showed the lowest. Meta-LLaMA produced the largest overall errors for Agreeableness (MAE = 1.68; RMSE = 1.95); while GPT-4.1-Mini achieved the smallest errors on Openness (MAE = 0.54; RMSE = 0.73).

Figures 6 and 7 compare binned trait distributions (Low, Moderate, High). All models tended to overpredict Moderate and High scores while underestimating Low scores, particularly for Agreeableness and Conscientiousness, with overpredictions in the High bin exceeding self-report reference by nearly 300 counts. Openness and Neuroticism showed relatively better alignment. CoT prompting produced minimal distributional patterns for GPT-4.1-Mini, GPT-5-Mini, and DeepSeek, while Meta-LLaMA shifted toward more concentrated Moderate-level predictions rather than improving overall alignment.

Figure 8 summarizes the exact match rates, off-by-one accuracy, and Cohen’s kappa scores for Big Five trait. Exact match rates ranged from 23% to 49%, with GPT-4.1-Mini (zero-shot) achieving the highest values for Openness (0.49), Neuroticism (0.43), and Extraversion (0.35). The lowest exact matches occurred under Meta-LLaMA (CoT) for Agreeableness and Neuroticism (0.23).

Off-by-one accuracy exceeded 0.70 for most traits, with Meta-LLaMA (CoT) reaching 1.00 on three traits and GPT-4.1-Mini (zero-shot) reaching 0.98 for Openness. The lowest Off-by-one accuracy was observed for GPT5-Mini (Zero-shot) on Agreeableness (0.57). Cohen’s kappa values were near zero or negative for all models and traits, with the highest value being k = 0.11 (GPT-4.1-Mini CoT, Conscientiousness), and the lowest k = −0.07 (GPT5-Mini, Zero-shot, Extraversion). Pearson r, Spearman ρ, and 95% confidence intervals are reported in Supplementary Material Table S4.

Model Consistency and Inter-Model AgreementWe first evaluated model inference stability by repeating inferences three times using identical interview transcripts under fixed model-specific settings for GPT-4.1-Mini (Supplementary Material Table S5). At the BFI-10 item level, most items showed high inference stability across repeated runs, with ICCs between 0.86 and 0.93. The highest reliability was observed for BFI-6 (“is outgoing, sociable”) and BFI-8 (“does a thorough job”), both at 0.93. BFI_2 (“is generally trusting”) and BFI_9 (“gets nervous easily”) also showed excellent reliability (ICCs = 0.92 and 0.91, respectively). BFI_1 (“is reserved”) and BFI_10 (“has an active imagination”) followed 0.90. The lowest reliabilities were for BFI-4 (0.88), BFI-7 (0.86), BFI-3 (0.75), and BFI-5 (0.61), with the latter indicating relatively poor consistency.

At the aggregated Big Five trait level (Supplementary Material Table S6), inference stability was consistently high across all dimensions, with ICCs exceeding 0.80. Conscientiousness achieved perfect reliability (ICC = 1.00), followed by Extraversion (0.97), Neuroticism (0.95), Openness (0.88) and Agreeableness (0.81).

We next assessed inter-model agreement using ICC (2,1), treating models as random-effect raters and participants as targets. At the BFI-10 item level, inter-model agreement was generally low, with ICC (2,1) values ranging from near zero to approximately 0.26 (Supplementary Material Table S7).

At the Big Five-dimension level, inter-model agreement was substantially higher under zero-shot prompting, with ICC (2,1) values ranging from 0.54 to 0.76. Neuroticism exhibited the highest agreement (ICC = 0.76), followed by Openness (ICC = 0.65) and Conscientiousness (ICC = 0.74) (Supplementary Material Table S8). In contrast, CoT prompting markedly reduced inter-model agreement, with ICC values ranging from 0.11 to 0.34. Under CoT prompting, Neuroticism again showed the highest agreement (ICC = 0.34), followed by Extraversion (ICC = 0.21), while other traits exhibited low consistency across models (Supplementary Material Table S9).

Ablation AnalysisWe conducted an ablation study using GPT-4.1-Mini to examine how input context length (short: 100 tokens; medium: 1000 tokens; full context) affects Big Five trait prediction. Medium-length input yields the highest Pearson correlations across all traits, with peaks at Agreeableness (r = 0.219) and Conscientiousness (r = 0.214). In contrast, short-input conditions produced substantially lower correlations, with most traits falling below r = 0.06 and Extraversion showing a negative correlation (Supplementary Material Figure S1).

Longer input contexts increased RMSE. Full-context input resulted in the highest RMSE for Agreeableness (1.63), Conscientiousness (1.59), and Neuroticism (1.46). Conversely, short-input conditions got the lowest RMSE for Extraversion (1.19) and Openness (0.79) (Supplementary Material Figure S2).

Figure 9 illustrates binned traits distribution across input lengths. Predictions in the moderate bin aligned most closely with self-report reference. For Conscientiousness and Agreeableness, high scores were consistently overestimated and low scores underestimated. Under short-context input, Openness deviated sharply, with over 200 predictions in the high bin compared to 50 in the self-report reference. Similar trends were observed for Extraversion. Medium and full-context conditions showed better alignment with self-report reference.

Figure 10 shows that exact match rates improved modestly with increased context length. The greatest gains were observed for Openness (from 0.24 to 0.49) and Neuroticism (from 0.34 to 0.40). Off-by-one bin accuracy remained high (≥0.64) across all conditions. Medium and full-context inputs consistently outperformed short-context input, with the highest off-by-one rate observed for Openness (0.94, medium; 0.96, full). Cohen’s kappa values remained low overall (<0.01), although medium- and full-context inputs yielded slightly higher values than short input. The highest k was for Conscientiousness (κ = 0.088, full), while the lowest was for Openness (κ = −0.059, short).

This study provides one of the few systematic evaluations of whether contemporary LLMs can infer personality-related traits from spoken responses to semi-structured interviews. Across analyses, model predictions were internally consistent but showed weak correspondence with BFI-10 self-report scores when inferred from interview narratives. Below, we discuss the implications of these findings across the four research questions and situate them within recent work on cognitive modeling and AI evaluation.

LLM Accuracy in Personality Prediction (RQ1)Model outputs were internally consistent but only minimally aligned with true personality profiles. This pattern echoes observations from Ullman and others, who have shown that LLMs often rely on surface level linguistic statistics rather than constructing internal mental-state representations [39]. In our setting, the same dynamic likely underlies consistently biased trait estimates: models may repeatedly map emotional or descriptive language to stable traits, even when such patterns do not hold in psychological reality. Trait inference inherently requires abstraction beyond any single event or narrative, a capacity current models appear to lack. These patterns suggest that LLMs capture explicit behavioral signals rather than latent psychological constructs, consistent with prior work on LLM-based trait inference from counseling or social media data [40,41].

Prompting Strategy and the Role of Reasoning (RQ2)The specific CoT prompting strategy evaluated in this study did not yield systematic improvements in accuracy, indicating that explicit reasoning steps cannot compensate for absent conceptual grounding. Results from the GAIA benchmark similarly show that LLMs struggle with tasks requiring multi-step reasoning, calibration, and contextual integration, all of which are prerequisites for accurately inferring personality from distributed cues [42]. The CoT explanations produced by the models often highlighted salient but misleading features, reinforcing the view that LLM “reasoning” remains stylistic rather than inferential. Importantly, this conclusion is limited to the fixed, generic CoT template evaluated here and does not preclude potential benefits from alternative or trait-specific prompting designs.

Distributional Alignment and Systematic Biases (RQ3)Predicted trait distributions systematically deviated from actual human distributions, with overestimation of moderate and high scores and underestimation of low scores. This bias resembles the “default persona” phenomenon documented by DeepMind (2025) [43], whereby instruction-tuned models generate stylized profiles that converge toward prosocial, articulate, or emotionally expressive norms. Such systematic biases, likely arising from instruction-tuning and normative language priors rather than dataset imbalance, reduce categorical accuracy even when off-by-one error appears acceptable, underscoring poor calibration and the absence of grounding in true population variability.

Model Stability, Inter-Model Agreement, and Input Length Effects (RQ4)To better interpret model performance, we examined inference stability, cross-model agreement, and the role of input context. Model outputs were highly stable across repeated runs under fixed settings, indicating that performance variability was not driven by stochastic decoding. However, this stability did not translate into agreement across models, particularly at the fine-grained BFI-10 item level, suggesting that different LLMs may rely on distinct linguistic heuristics when mapping conversational language to personality constructs.

At a broader trait level, inter-model agreement was higher under zero-shot prompting but declined substantially with CoT prompting, indicating that explicit reasoning scaffolds may amplify model-specific interpretations rather than promote shared trait representations. Increasing input context length modestly improved alignment with self-report measures but also increased prediction variance, highlighting a trade-off between contextual richness and reliability.

Variations between momentary states and stable traits may partly account for the patterns in model performance. Our interviews captured the expression of states which can include enduring traits but can also include normative deviations based on context or circumstances. Although these interviews are demonstrated to elicit responses highly predictive of a broad set of psychological processes, they are representative of the individual experiences reported in one moment in time. Consequently, LLMs relying on surface-level linguistic features may confound some reactivity present in transient emotional narratives as indicators of stable personality dispositions.

LLMs may therefore interpret interview content at face value, treating situational or emotionally charged narratives as indicators of enduring personality traits. In the TTC_5002 example (Supplementary Material Box S3), the participant’s highly social week—filled with recruitment events, group activities, and interactions with friends—led the model to infer very high Extraversion (4.5), even though such behavior may simply reflect a temporary, event-driven state rather than the participant’s typical disposition (self-report reference: 2.0). Similarly, the model inferred elevated Conscientiousness by focusing on mentions of completed assignments or structured activities, while overlooking contradictory cues such as waking up late or feeling disorganized signals that reflect momentary states rather than stable patterns. This challenge is also common in conventional psychological assessment frameworks and represents a limitation to most methods.

More broadly, when transcripts contain emotionally salient or socially intense episodes, LLMs tend to overgeneralize from episodic states and map them onto stable trait judgments. Addressing this trait–state gap will be essential for future modeling efforts. Differentiating “how someone felt in this particular story” from “how they typically behave” can be conceptually straightforward for humans but remains largely inaccessible to current LLMs. Without mechanisms to disentangle episodic emotion, narrative style, and contextual pressures from enduring dispositions, LLM-based personality inference will remain fundamentally limited.

Several limitations warrant discussion. First, the transcripts emphasize situational narratives, which may limit the amount of trait-relevant available to both humans and models. Second, the BFI-10, while practical, provides coarse-grained measurement that may cap achievable accuracy and also suffer from measurement error. Third, LLMs are trained on general internet text, which differs substantially from emotional and event-focused interviews, potentially leading to systematic miscalibration. Additionally, our analyses relied solely on textual data; many cues used in human personality judgment, such as prosody, affective tone, conversational dynamics were absent. Finally, architectural and training differences across models further constrain the generalizability of our findings.

Although LLMs are trained on vast amounts of human-generated data, their general-purpose pretraining typically lacks direct supervision from structured personality assessments or domain-specific trait annotations. This poses challenges for modeling personality-related constructs from language, which are theoretically nuanced and sensitive to contextual and situational variation. Moreover, inferring personality from naturalistic behavior is difficult even for trained professionals, underscoring the need for carefully designed and task-specific modeling strategies.

Future approaches explore cognitively grounded prompting techniques, such as meta-cognitive scaffolding [44] or self-reflective agentic reasoning [45] frameworks, to better support trait-level abstraction. Additionally, incorporating domain-adaptive training regimes or retrieval-augmented prompting from personality-rich corpora (e.g., psychological interview transcripts, diary studies) may enhance model alignment with theoretical constructs. As LLMs are increasingly deployed in mental health, education, and personalization contexts, future research should prioritize stable, interpretable, and ethically grounded mechanisms for trait modeling under naturalistic language conditions.

This study provides a comprehensive evaluation of whether contemporary LLMs can infer stable personality traits from semi-structured interviews. Across models, prompting strategies, and evaluation metrics, current LLMs produced internally consistent but weakly aligned personality estimates relative to self-reported measures. These limitations arise not only from statistical miscalibration and distributional bias, but also from a deeper conceptual mismatch: interview narratives reflect individual report of current experiences and situational states across a variety of contexts. Without mechanisms to disentangle episodic emotion, narrative style, and contextual pressures from enduring dispositions, LLMs may systematically overgeneralize from state-like linguistic cues and misattribute them to trait-level constructs.

Our findings highlight the need for theoretical grounding in the design of LLM-based personality inference systems. Approaches that explicitly integrate state–trait distinctions, employ richer psychometric instrumentation, or aggregate behavioral evidence across multiple interactions may better support dispositional reasoning. As LLMs continue to be deployed in mental health, education, and personalization contexts, this work underscores the importance of cautious interpretation, improved calibration, and ethically grounded development. Reliable personality inference remains an open challenge that will require closer integration between psychological theory and computational modeling.

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it involved secondary analysis of de-identified data and posed minimal risk to participants.

Declaration of Helsinki STROBE Reporting GuidelineThis study adhered to the Helsinki Declaration. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline was followed.

The following supplementary materials are available online: Supplementary Analyses and Materials for Benchmarking Personality Inference in Large Language Models Using Real-World Conversations.

The dataset used in this study is not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conceptualization, JZ; Methodology, JZ, XL and JM; Software, JZ, XL and JM; Formal Analysis, JZ; Investigation, JZ; Data Curation, JZ; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, JZ; Writing—Review & Editing, JZ and KGC; Visualization, JZ; Supervision, RJ.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. This research was conducted independently and without any commercial or financial involvement that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

This research received no external funding.

The author thanks colleagues for helpful discussions and feedback.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

Zhu J, Li X, Maharjan J, Coifman KG, Jin R. Benchmarking personality inference in large language models using real-world conversations. J Psychiatry Brain Sci. 2025;10(6):e250020. https://doi.org/10.20900/jpbs.20250020.

Copyright © Hapres Co., Ltd. Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions