Location: Home >> Detail

TOTAL VIEWS

Crop Breed Genet Genom. 2026;8(1):e260004. https://doi.org/10.20900/cbgg20260004

1 Ottawa Research and Development Centre, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, 960 Carling Avenue, Ottawa, ON K1A 0C6, Canada

2 Crop Development Centre, Department of Plant Sciences, University of Saskatchewan, 51 Campus Drive, Saskatoon, SK S7N 5A8, Canada

* Correspondence: Frank M. You

Genomic selection (GS) is a core strategy in modern breeding programs, yet the rapid expansion of statistical, machine learning (ML), and deep learning (DL) models has made systematic evaluation and practical deployment increasingly challenging. To address these issues, we developed MultiGS, a unified and user-friendly framework that integrates linear, ML, DL, hybrid, and ensemble GS models within a standardized and computationally efficient workflow. MultiGS is implemented through two complementary pipelines: MultiGS-R, a Java/R pipeline implementing 12 statistical and ML models, and MultiGS-P, a Python pipeline integrating 17 models including five linear models, three ML approaches, and nine recently developed DL architectures. We benchmarked MultiGS using wheat, maize, and flax datasets representing contrasting prediction scenarios. Wheat and maize were evaluated using random training–test splits within the same population, reflecting suitable conditions for assessing model capacity and scalability. Under these scenarios, several DL, hybrid, and ensemble models achieved prediction accuracies comparable to or exceeding those of RR-BLUP and GBLUP. In contrast, the flax dataset represented a true across-population prediction scenario with limited training set size and strong population structure. In this challenging context, classical linear models provided stable baselines, while a subset of DL architectures, particularly graph-based models and BLUP-integrated hybrids, demonstrated comparatively improved generalization across populations. Comparisons with previously published DL tools showed that models implemented in MultiGS achieved comparable or improved prediction accuracies while requiring lower computational cost, enabling routine retraining and large-scale evaluation. Collectively, MultiGS supports scenario-specific model selection and provides a practical platform for deploying genomic prediction under realistic breeding conditions. The software is freely available on GitHub (https://github.com/AAFC-ORDC-Crop-Bioinformatics/MultiGS).

APP, across-population prediction; BL, Bayesian LASSO; BLUP, best linear unbiased prediction; BN, batch normalization; BRR, Bayesian ridge regression; CNN, convolutional neural network; Conv, convolution (layer); CV, cross-validation; DL, deep learning; FC, fully connected (layer); FFN, feed-forward network; GBLUP, Genomic BLUP; GCN, graph convolutional network; GAT, graph attention network; GEBV, genomic estimated breeding value; GELU, Gaussian Error Linear Unit; GNN, graph neural networks; GS, genomic selection; HAP, haplotype; LD, linkage disequilibrium; KNN, k-nearest neighbors; MHA, multi-head attention; ML, machine learning; MLP, multilayer perceptron; OOF, out-of-fold; PC, principal component; PCA, principal component analysis; ReLU, rectified linear unit; RFR, Random Forest Regression; RR-BLUP, Ridge Regression Best Linear Unbiased Prediction; RKHS, Reproducing Kernel Hilbert Space; SAGE, sample and aggregate (GraphSAGE); SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; VCF, variant call file; TKW, thousand-kernel weight; GW, grain width; GH, grain hardness; GP, grain protein; GL, grain length; DTT, days to tassel; PH, plant height; EW, ear weight; DTM, days to maturity; OIL, oil content

Genomic selection (GS) has become a core strategy in modern plant and animal breeding, enabling the prediction of breeding values using genome-wide markers and accelerating genetic gain through reduced cycle time [1,2]. Since its introduction, a wide range of statistical, machine learning (ML), and deep learning (DL) models have been developed to improve prediction accuracy (PA), typically measured as the Pearson correlation coefficient between predicted and observed phenotypes. Traditional linear models such as Ridge Regression BLUP (RR-BLUP) and Genomic BLUP (GBLUP) remain widely adopted due to their simplicity, computational efficiency, and strong baseline performance [3,4], while Bayesian approaches, including Bayesian Ridge Regression (BRR), Bayesian LASSO (BL), and BayesA/B/C, provide additional flexibility in modeling heterogeneous marker-effect distributions [5,6].

ML approaches such as random forest, support vector machines, gradient boosting, and regularized regression have expanded the analytical landscape of GS by capturing nonlinear relationships and higher-order interactions among markers [7,8]. More recently, DL architectures, including multilayer perceptrons (MLP), convolutional neural networks (CNN), recurrent networks, attention-based models, transformers, and graph neural networks (GNNs), have shown promise for capturing nonlinear effects, epistasis, and structural dependencies among markers [9–12]. This has led to the development of numerous DL-based GS methods, such as DeepGS [9], G2PDeep [13], DeepGP [14], DNNGP [15], GPformer [16], Cropformer [17], GEFormer [18], iADEP [19], WheatGP [20], SoyDNGP [21] and DPCformer [22], each exploring different architectural designs and reporting improvements relative to traditional models under specific datasets or validation schemes.

Despite this rapid methodological progress, several limitations continue to hinder the broad adoption of DL-based GS methods in practical breeding pipelines. Many existing tools provide only partial or research-oriented implementations, with fragmented codebases, inconsistencies between published descriptions and actual source code, limited documentation, or incomplete end-to-end workflows. As a result, reproducibility and usability are often compromised, making integration into routine breeding workflows difficult. Moreover, many DL tools require substantial expertise in Python, PyTorch [23], graphics processing unit (GPU) computing, or Unix/Linux environments—skills that are uncommon among breeders and applied geneticists. Consequently, although DL models show promise, their accessibility to breeding programs remains limited.

A second challenge arises from inconsistent benchmarking practices across studies. Reported improvements over RR-BLUP, GBLUP, or other baselines often depend on differences in software implementations, preprocessing procedures, hyperparameter choices, or validation strategies. Based on our experience implementing both R- and Python-based versions of standard GS models, even nominally identical methods can yield substantially different prediction accuracies depending on software environments and analytical settings. These inconsistencies make it difficult to determine whether a DL model consistently outperforms existing approaches or simply performs well under a specific configuration. The field therefore lacks a unified, reproducible benchmarking framework that supports diverse model families under standardized evaluation procedures.

To address these limitations, we developed MultiGS, a pair of complementary, user-friendly genomic prediction platforms that: (1) integrate a broad spectrum of GS models, ranging from classical linear mixed models to advanced ML, DL, hybrid and ensemble architectures; (2) provide standardized workflows for data preprocessing, cross-validation (CV), across-population prediction (APP), and post-analysis; and (3) support multiple marker types, including single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP), haplotypes (HAP), and principal components (PC). In this study, we describe the design and implementation of the MultiGS framework and evaluate its performance across multiple datasets representing distinct breeding scenarios. Our results show that the DL models implemented within the MultiGS framework can achieve prediction accuracies (PAs) comparable to RR-BLUP and, in some settings, exceed those of GBLUP, consistent with recent evidence that DL approaches can be competitive with traditional GS models under appropriate conditions. By integrating DL models alongside established linear and ML approaches within a unified and reproducible framework, MultiGS emphasizes scenario-specific model selection rather than advocating a single optimal method. Collectively, MultiGS bridges methodological innovation and practical usability, offering an integrated platform to support genomic selection research and facilitating deployment in real-world breeding programs.

The MultiGS framework was developed to provide an integrated and reproducible platform for GS as the field expands from traditional mixed models towards increasingly diverse ML and DL approaches. In particular, MultiGS places strong emphasis on the systematic evaluation of nine DL architectures that capture nonlinear, local, and graph-structured genotype–phenotype relationships beyond the assumptions of classical linear methods. Existing GS pipelines often require users to navigate multiple software tools with inconsistent workflows and incompatible preprocessing procedures, making fair comparison and practical deployment of DL models especially challenging. MultiGS resolves these limitations by offering a unified ecosystem that standardizes data handling, model execution, cross-validation, and result summarization across statistical, ML, and DL models. The framework supports three marker types derived from SNP genotypes: SNP, HAP, and PC, and adopts a consistent input–output structure across all implemented algorithms, enabling direct benchmarking of classical models against advanced DL architectures.

MultiGS is organized into two complementary pipelines. MultiGS-R provides access to classical GS and Bayesian methods implemented in R serving as robust baselines widely used in breeding programs. MultiGS-P substantially extends the analytical scope by implementing advanced ML methods and nine DL models, including fully connected networks, convolution–attention hybrids, graph neural networks, and BLUP-integrated hybrid architectures. These DL models were designed to explicitly target key challenges in GS, such as nonlinear marker effects, local linkage disequilibrium (LD) patterns, and population structure, within a common and reproducible framework.

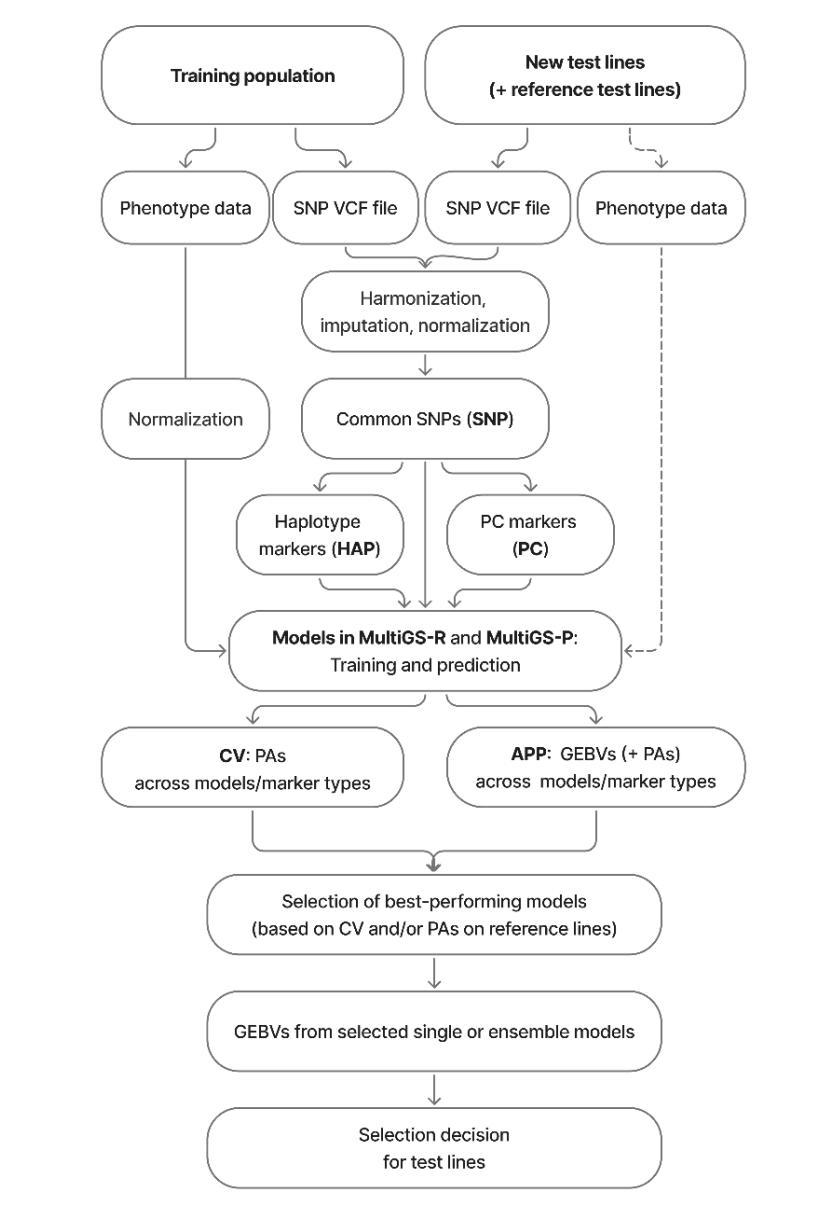

Both pipelines share the same design logic, allowing users to evaluate linear, ML, and DL models under identical preprocessing steps, training configurations, and accuracy metrics. Detailed descriptions of the R and Python pipelines are shown in Figure 1. To ensure user-friendliness, MultiGS employs a standardized input–output format controlled by a configuration file. Users can flexibly select any combination of models, marker types, and evaluation modes (model benchmarking or prediction) simply by modifying configuration flags, without altering their data preparation workflow. This design enables breeders and researchers to focus on biological interpretation and breeding decisions while facilitating rigorous assessment of advanced DL models alongside established GS approaches.

Figure 1. Schematic overview of the genomic prediction platform used to predict the genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs) of new breeding lines with MultiGS-R and MultiGS-P. The reference test lines with phenotypic data and the dotted box containing phenotypic data from the test population are optional and used only for model evaluation and model selection when available.

Figure 1. Schematic overview of the genomic prediction platform used to predict the genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs) of new breeding lines with MultiGS-R and MultiGS-P. The reference test lines with phenotypic data and the dotted box containing phenotypic data from the test population are optional and used only for model evaluation and model selection when available.

MultiGS-R is the R-based pipeline for statistical and ML models. It integrates twelve widely used GS models through the rrBLUP [4], BGLR [6], e1071 [24], and randomForest [25] packages. These include linear mixed models such as RR-BLUP and GBLUP, Bayesian regression models including BRR, BL, and BayesA/B/C, random forest algorithms, SVM, and RKHS methods (Table S1). MultiGS-R automates the core steps of GS analysis—genotype and phenotype preprocessing, model training, prediction, and accuracy assessment while maintaining consistent output formats across models. This pipeline provides a stable and accessible environment for breeders and researchers who require reliable and interpretable models without the need for extensive scripting.

MultiGS-PMultiGS-P implements an extensive suite of ML and DL models using Python, scikit-learn [26], and PyTorch [23]. The pipeline includes linear and regularized models (RRBLUP-equivalent Ridge, ElasticNet, and BRR), tree-based learners (Random Forest Regression), and gradient boosting methods (XGBoost and LightGBM) (Table S2). In addition to these conventional ML approaches, MultiGS-P implements nine recently developed DL architectures, ranging from fully connected networks and convolution–attention hybrids to multiple graph neural network variants (Table 1). The pipeline further integrates hybrid methods that combine RR-BLUP with deep networks (DeepResBLUP and DeepBLUP), as well as a stacking-based ensemble learner (EnsembleGS) capable of fusing predictions from arbitrary base models (Table 1). Together, this collection provides a comprehensive modeling environment in which additive, nonlinear, LD-aware, graph-structured, and hybrid genotype–phenotype relationships can be evaluated within a unified and reproducible workflow.

All DL models were systematically tuned during development to ensure stable training and competitive performance across datasets. The default hyperparameters for all models implemented in MultiGS-P are provided in the template configuration files and are summarized in Table S3.

The DL architectures are grouped into fully connected, graph-based, hybrid, and BLUP-integrated categories. Each architecture is described in the Supplementary Methods with documentation of its design rationale and intended uses (Figures S1 and S2). All ML and DL models in MultiGS-P are fully configurable through a centralized configuration file (Table S3), allowing users to adjust hyperparameters, model depth, learning schedules, and regularization settings without modifying source code. This design facilitates systematic benchmarking and fair comparison across diverse model classes while supporting flexible adaptation to a range of datasets and breeding scenarios.

Hyperparameter Tuning of Deep-Learning ModelsAll DL models were tuned during development using the flax training dataset, which represents a challenging scenario characterized by a small training population and strong population structure. This setting more closely reflects realistic breeding conditions than within-population validation and therefore provides a conservative basis for model configuration. Hyperparameters identified under this conservative setting were subsequently applied uniformly to all datasets, including wheat2000, maize6000, and flax287. No dataset- or trait-specific tuning was performed, ensuring fair and consistent comparison among model classes.

Although these hyperparameters are not necessarily optimal for every species or dataset, this strategy was adopted to avoid dataset-specific manual tuning that could introduce bias and compromise comparability across models. Moreover, this approach reflects a realistic usage scenario in breeding programs, where extensive hyperparameter optimization is often impractical due to limited computational resources or technical expertise.

Hyperparameter tuning was conducted using a grid search strategy, and the resulting default settings are provided in the template configuration files and summarized in Table S3. For users who wish to further optimize model performance for specific datasets, a utility script (hyperparameter_optimizer.py) is provided to facilitate targeted tuning of key model parameters.

Marker TypesMultiGS supports three genomic feature representations, SNP, HAP, and PC, allowing users to evaluate model performance across alternative marker types. Here, “SNP” is used as a representative marker category and encompasses any biallelic or numerically encoded molecular markers compatible with matrix-based genomic prediction models, including genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS), diversity arrays technology (DArT), simple sequence repeat (SSR), and amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers. These marker types capture complementary aspects of genomic variation and provide flexibility for modeling different genetic architectures.

The SNP marker type uses the raw genotype matrix, encoding markers as additive allele counts. Although referred to here as SNP-based, this representation can accommodate any bi-allelic or multi-allelic markers derived from different genotyping technologies, provided they are numerically encoded. This marker type is the most widely used in genomic selection and serves as the baseline input for most models.

The HAP marker type aggregates adjacent SNPs into haplotype blocks, enabling models to capture local linkage-phase information and multi-allelic patterns that may correlate more strongly with causal loci. Haplotype markers are particularly useful in regions with strong LD or when phased or block-based genotype data are available. Both pipelines used additive dosage coding with values 0, 1, and 2: code 0 (0/0) for homozygous reference alleles, code 1 (0/1, 0/2, …) for heterozygous genotypes with one alternative allele, and code 2 (1/1, 2/2, …) for homozygous alternative alleles. Missing data (./.) are assigned code –1 and are imputed using the mean algorithm or Beagle software [27]. Haplotype blocks were estimated with the rtm-gwas-snpldb tool in RTM-GWAS v2020.0 [28], which applies the Haploview “Gabriel” confidence-interval algorithm [29,30]. This algorithm identifies haplotype blocks based on statistically supported LD confidence intervals and has been widely adopted for defining robust LD blocks. Pairwise LD was measured using D’ with 95% confidence intervals, and haplotype blocks were defined when ≥95% of informative pairs were in strong LD (CI(D’) lower ≥ 0.70, upper ≥ 0.98).

The PC marker type summarizes genome-wide marker information using PCs derived from SNP data. PCs capture major population structure and relatedness patterns while reducing dimensionality. This representation provides a compact genomic representation and may improve stability or computational efficiency in certain models. The first N PCs explaining 95% (configurable) of the total variance are retained for prediction. The number of retained PCs varied across datasets but typically ranged between ~20 and 200.

All three marker types are constructed automatically within both MultiGS pipelines, ensuring consistent preprocessing and compatibility across model families.

Model EvaluationMultiGS provides standardized evaluation procedures to ensure reliable comparison of models, marker types, and data partitions. Both pipelines implement CV schemes commonly used in genomic prediction studies, including random k-fold CV for assessing general predictive performance within populations. In addition, structured CV options are supported for breeding programs involving multiple families or subpopulations. CV routines are fully automated, with users specifying fold number and seed settings to maintain reproducibility. Beyond within-population evaluation, MultiGS explicitly supports across-population prediction (APP), a realistic breeding scenario in which training and target populations differ genetically. In APP mode, models are trained using a designated reference population and evaluated on an independent target population without phenotypic information during training.

Prediction accuracy (PA) was consistently quantified as Pearson’s correlation coefficient between predicted and observed values. This metric was used uniformly across all models, marker types, and datasets to enable direct comparison. MultiGS also generates prediction summaries and visualization files to facilitate rapid comparison of model performance. All result formats are identical across the R and Python pipelines, enabling seamless benchmarking of statistical, ML, and DL approaches.

Case StudiesTo evaluate the performance of the models implemented in the MultiGS pipelines, three genomic and phenotypic datasets, wheat, maize, and flax, were analyzed. These datasets were selected to represent contrasting breeding and prediction scenarios, ranging from within-population evaluation to true across-population prediction.

The wheat dataset consisted of 2403 Iranian bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) landrace accessions conserved in the CIMMYT Wheat Gene Bank (https://hdl.handle.net/11529/10548918) [31]. Genotyping was performed using 33,709 DArTseq presence/absence markers, coded as 1 (allele present) or 0 (allele absent). Five traits, thousand-kernel weight (TKW), grain width (GW), grain hardness (GH), grain protein (GP), and grain length (GL), were evaluated. After removing accessions with missing phenotypes, the remaining 2000 accessions were randomly divided into a training population of 1,600 and a testing population of 400 (80:20 ratio). After filtering using minor allele frequency ≥ 5%; call rate ≥ 80%, the retained 9927 markers were converted to VCF format for genomic prediction analyses. This dataset is hereafter referred to as wheat2000.

The maize dataset was derived from the CUBIC hybrid population [32]. In total, 6210 F₁ hybrids (207 female × 30 male) were evaluated across five environments in China during the 2015 growing season. Three agronomic traits, days to tassel (DTT), plant height (PH), and ear weight (EW), were measured, and best linear unbiased predictions (BLUPs) were calculated across environments. Genomic data consisted of 10,000 SNPs randomly sampled from ~4.5 million imputed markers available through the ZEAMAP repository (https://ftp2.cngb.org/pub/CNSA/data3/CNP0001565/zeamap/99_MaizegoResources/01_CUBIC_related/). After removing hybrids missing genotypic or phenotypic records, the dataset comprised 5831 maize hybrids. These hybrids were randomly partitioned into a training population of 4,664 hybrids (80%) and a testing population of 1167 hybrids (20%). This dataset is hereafter referred to as maize6000.

To evaluate across-population prediction performance, a flax dataset comprising 278 linseed accessions genotyped by whole-genome sequencing was used as the training population (flax287) [33–35]. Approximately 1.7 million SNPs were available for model training. The test population consisted of 260 inbred lines derived from multiple biparental populations [33], representing a realistic breeding scenario in which prediction targets differ substantially from the training population. These test lines were re-genotyped by mapping short paired-end reads to the latest flax reference genome, CDC Bethune v3.0 (NCBI accession JAZBJT000000000; You et al., in preparation), yielding 43,179 SNPs, of which 33,895 were shared with the training populations and used for genomic prediction. Three key agronomic traits, days to maturity (DTM), oil content (OIL), and PH, were evaluated.

Genetic diversity and population differentiation between training and test sets across the three datasets are summarized in Table S4. Wheat2000 and Maize6000 exhibited negligible genetic differentiation between training and test populations (FST ≈ 0), consistent with random within-population sampling. However, flax287 exhibited strong population divergence (FST = 0.27), reflecting a true across-population prediction scenario. Expected heterozygosity (He) was high in maize6000 (~0.38) but markedly lower in wheat2000 and flax287 (~0.01–0.02), highlighting substantial differences in genetic diversity among datasets.

To benchmark the performance of the MultiGS framework against existing DL–based GS approaches, we selected four publicly available GS tools representing diverse neural-network architectures: DeepGS (convolutional neural networks) [9], CropFormer (CNN integrated with self-attention) [17], WheatGP (CNN-LSTM–based feature extractors) [20], and DPCFormer [22]. Because these tools differ in their required input formats, preprocessing workflows, and output interfaces, direct comparison is not straightforward. To ensure consistent evaluation across models, we developed customized wrapper programs for each tool. These wrappers harmonized SNP marker data and phenotypic inputs, including: (i) aligning samples between genotype and phenotype files, (ii) identifying common markers between training and testing sets, (iii) converting VCF, comma separated value (CSV), or matrix formats into tool-specific input structures, and (iv) standardizing prediction outputs for downstream comparisons. All tools were run using identical training/test splits and the same set of single-trait prediction tasks. This unified preprocessing and execution framework ensures a fair, reproducible comparison between MultiGS models and previously published GS methods regardless of their heterogeneous interfaces.

To ensure fair comparison with previously published DL tools that require fixed input dimensions, dataset-specific adaptations were applied where necessary. For WheatGP, the original implementation hard-coded the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) input size as lstm_dim = 10,080, corresponding to the reference dataset used in the original study. However, the effective dimensionality of the LSTM layer depends on the number of markers provided as input. To enable application across datasets with varying SNP counts, we modified the implementation by replacing the fixed input size with a dynamic formulation, lstm_dim = 8(gi - 4), where gi denotes the number of SNP markers in the i-th group (five groups in total, as defined in WheatGP). This modification allows the LSTM input dimension to scale automatically with the number of available markers, enabling consistent application across datasets without altering model structure.

For CropFormer, the number of input markers is fixed at 10,000 by design. To satisfy this constraint, random SNP subsetting or zero-padding was applied as appropriate. Specifically, when datasets contained more than 10,000 markers, a random subset of 10,000 SNPs was sampled; when fewer markers were available, padding was used to reach the required input size. The same procedure was applied consistently across the wheat2000, maize6000, and flax287 datasets. Random sampling was performed using fixed random seeds to ensure reproducibility.

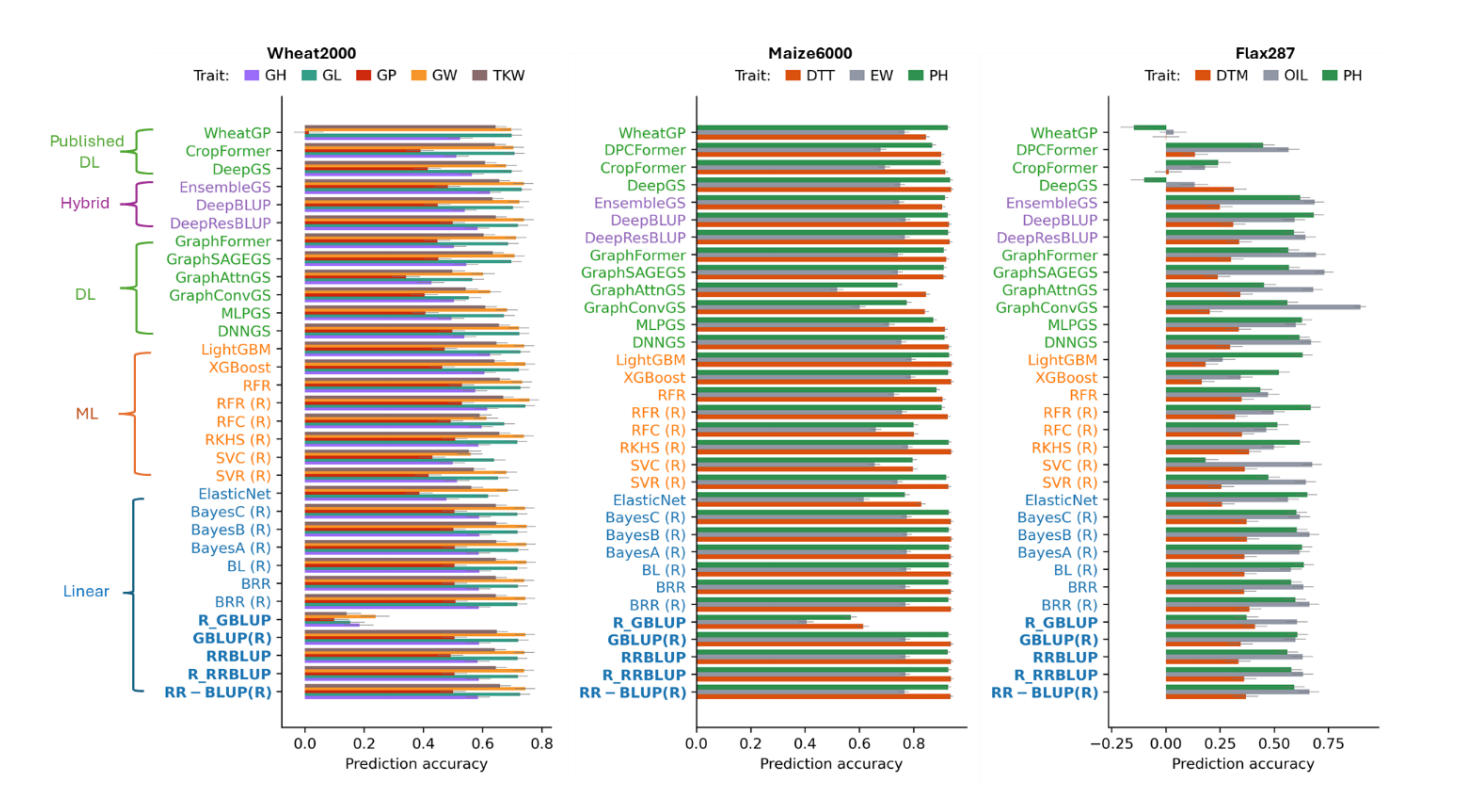

Using the wheat2000 dataset (1600 training and 400 independent test lines), we evaluated all models implemented in MultiGS-P and MultiGS-R and compared their performance with several published DL methods (Figure 2; Table S5). Linear mixed-model baselines (RR-BLUP, GBLUP, BRR) provided consistent reference performance across pipelines, with SNP-based PAs ranging from ~0.53 to 0.76 depending on trait. Nearly identical results across implementations confirmed reproducibility, while BGLR-based GBLUP slightly outperformed rrBLUP-based implementations, consistent with known differences in variance component estimation.

Several ML models achieved prediction accuracies comparable to or exceeding those of linear baselines. In particular, tree-based approaches such as Random Forest, XGBoost, and LightGBM frequently ranked among the strongest performers, achieving PAs of ~0.72–0.74 for GL and GW, comparable to or slightly exceeding RR-BLUP. ElasticNet showed stable but generally weaker performance and did not consistently outperform linear models.

DL models demonstrated competitive but trait-dependent performance. For high-heritability traits (GL, GW, TKW; h2 ≈ 0.83–0.88 [31]), most DL architectures achieved PAs comparable to those of top ML models and RR-BLUP (typically ~0.70–0.74). Among these, GraphSAGEGS and GraphFormer consistently outperformed other graph-based models, while DNNGS showed stable performance across traits. For lower-heritability traits (GH, GP), DL models slightly underperformed linear baselines but still achieved reasonable accuracies (~0.45–0.60).

Hybrid approaches integrating RR-BLUP with DL models ranked among the strongest DL-based models. DeepResBLUP matched or slightly exceeded RR-BLUP for GL, GW, and TKW, while DeepBLUP showed similarly robust performance. The stacking-based ensemble model, EnsembleGS, achieved consistently high accuracy across all traits (up to ~0.74), highlighting the benefit of combining complementary predictors.

Compared to published DL tools (DeepGS, CropFormer, WheatGP), the top MultiGS models achieved comparable or higher PAs across all traits. EnsembleGS, DeepResBLUP, and GraphSAGEGS consistently matched or outperformed DeepGS, while CropFormer and WheatGP showed more variable performance, particularly for GP.

Prediction Accuracy (PA) Across Models in the Maize6000 DatasetUsing the maize6000 dataset (4,664 training and 1,167 test lines), we evaluated 17 MultiGS-P and 12 MultiGS-R models using SNP-, HAP-, and PC-based markers across three traits (DTT, EW, PH) (Figure 2; Table S6). Linear baseline models again performed strongly, particularly for DTT and PH, with SNP- and HAP-based PAs consistently exceeding 0.92. For EW, prediction accuracies were lower (~0.76–0.77) but remained among the strongest results across model classes.

Tree-based ML models performed particularly well. XGBoost and LightGBM achieved accuracies up to ~0.94 for DTT and ~0.93 for PH, matching or slightly exceeding RR-BLUP, and ~0.78–0.79 for EW. In contrast, classification-oriented models (SVC, RFC) consistently underperformed for these continuous traits and were therefore less competitive.

Figure 2. Prediction accuracies (PAs) across 17 models implemented in MultiGS-P, 12 models implemented in MultiGS-R (indicated by “(R)”), and several previously published deep learning models for three datasets. Standard errors of PA are indicated on each bar. Models are categorized into Linear (blue), machine learning (orange), deep learning (green), and hybrid (purple). RR-BLUP and GBLUP are highlighted in bold as baseline models. Baseline models are shown in bold.

Figure 2. Prediction accuracies (PAs) across 17 models implemented in MultiGS-P, 12 models implemented in MultiGS-R (indicated by “(R)”), and several previously published deep learning models for three datasets. Standard errors of PA are indicated on each bar. Models are categorized into Linear (blue), machine learning (orange), deep learning (green), and hybrid (purple). RR-BLUP and GBLUP are highlighted in bold as baseline models. Baseline models are shown in bold.

DL models achieved accuracies comparable to linear baselines for DTT and PH, typically in the range of 0.91–0.93. GraphSAGEGS, GraphFormer, DeepResBLUP, and DeepBLUP consistently ranked among the strongest DL models. For EW, DL model performance was more variable; however, hybrid models (DeepResBLUP, DeepBLUP) matched RR-BLUP performance (~0.76–0.77), and GraphSAGEGS and EnsembleGS also performed competitively.

Relative to published DL tools (DeepGS, CropFormer, DPCFormer, WheatGP), the best MultiGS models achieved comparable or improved accuracies across all traits. EnsembleGS, DeepResBLUP, DeepBLUP, and GraphFormer matched or slightly exceeded DeepGS and CropFormer for DTT and PH, while DeepBLUP and DeepResBLUP performed comparably to the strongest previously published models for EW. Overall, MultiGS achieved competitive DL performance while supporting a broader and more flexible modeling environment.

Prediction Accuracy (PA) of Models for Across-Population Prediction in the Flax287 DatasetThe flax287 dataset represents a substantially more challenging scenario, combining a small training population (278 accessions) with prediction in genetically narrow biparental populations (260 lines) exhibiting strong population structure and genetic differentiation between training and test lines (Figure S3; Table S4). Across traits (DTM, OIL, PH), prediction accuracies were lower and more variable than in wheat2000 and maize6000 (Figure 2; Table S7). Haplotype-based models consistently outperformed SNP- and PC-based ones, reflecting strong LD structure in flax.

For DTM, all models showed limited predictive ability (HAP-based PAs ~0.20–0.41). Linear baselines were among the most stable performers (~0.33–0.41). ML models did not improve upon these results, and DL models showed high variability, with some architectures achieving baseline-level accuracy while others performed poorly or negatively. Previously published DL models exhibited similarly weak performance.

Conversely, the PAs for OIL were higher across all model families. Linear models achieved PAs of ~0.60–0.66, while several ML and DL models exceeded these baselines. DNNGS, GraphSAGEGS, GraphFormer, and EnsembleGS achieved accuracies up to ~0.70–0.75, and GraphConvGS reached the highest overall PA (~0.90). Hybrid models also performed well across marker types. Among previously published DL tools, only DPCFormer showed moderate performance, while others transferred poorly to this across-population setting.

For PH, baseline accuracies reached ~0.61, with several DL and hybrid models exceeding this level. DNNGS, GraphFormer, and DeepBLUP achieved PAs up to ~0.66–0.70, while ElasticNet and LightGBM also performed competitively. Previously published DL models again showed inconsistent or weak performance.

In summary, the flax results underscore the strong effects of training population size, population structure, and marker representation on genomic prediction. Linear models provided stable baselines, while selected DL and hybrid models, particularly those incorporating additive genetic priors or graph-based models, offered advantages for OIL and PH. These findings emphasize that DL benefits are trait- and context-dependent and support the value of a diverse modeling portfolio within the MultiGS framework.

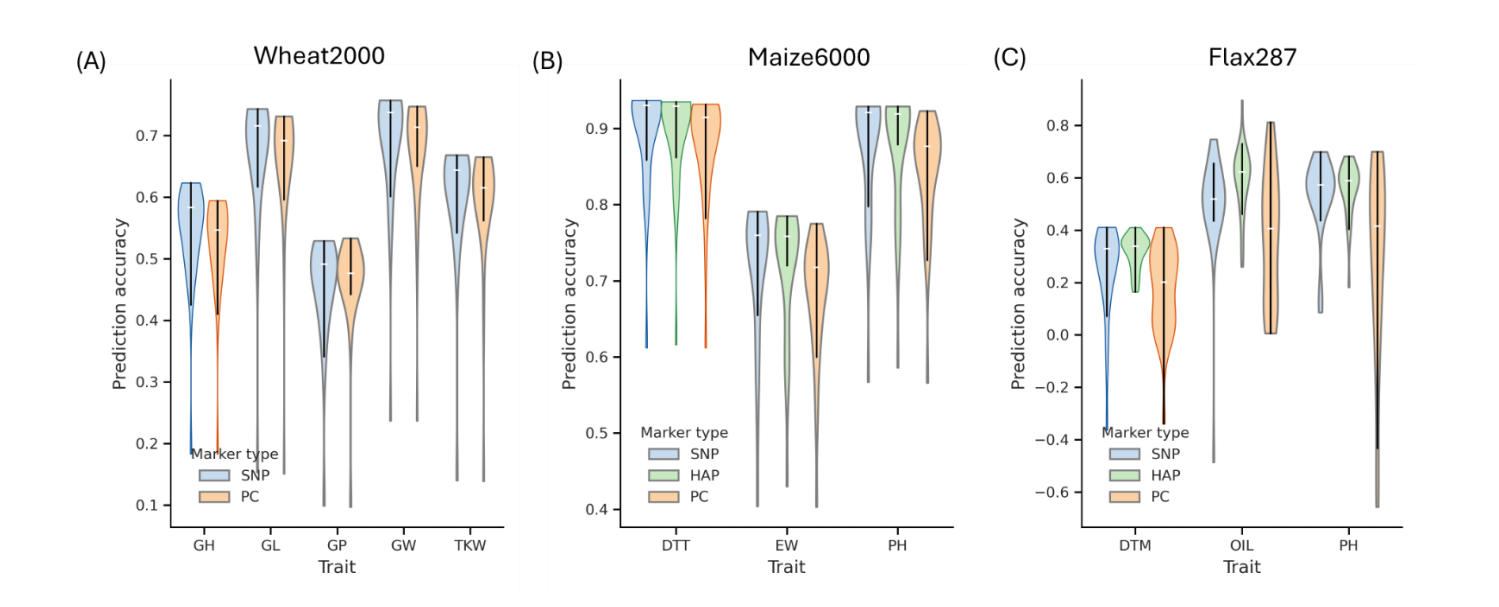

Effect of Marker Type on Prediction Accuracy (PA)Marker types had a consistent and measurable impact on PAs across models and datasets implemented in MultiGS with particularly strong effects observed in the flax287 across-population prediction scenario (Figure 3; Tables S5–S7). Across all 29 models implemented in MultiGS, HAP markers consistently matched or outperformed SNP- and PC-based markers when haplotypes could be derived.

In the wheat2000 dataset, where chromosome-level SNP coordinates were unavailable and haplotype construction was therefore not feasible, PAs based on SNPs and PCs were largely comparable. Across five traits, average PA differed only marginally between SNP- and PC-based models (mean PA: SNP = 0.597, PC = 0.586), with trait-specific differences typically within 0.01–0.02. These results indicate that both marker types captured similar predictive signals in this dataset.

In comparison, for the maize6000 and flax287 datasets, where HAP markers could be constructed, HAP markers consistently outperformed both SNP and PC markers. In maize, haplotype-based models achieved the highest PAs across all three traits, with an average PA of 0.831 compared with 0.800 for PC-based models. Improvements were particularly notable for EW (0.719 vs. 0.680) and PH (0.878 vs. 0.842), highlighting the value of capturing local linkage disequilibrium (LD) in a genetically diverse hybrid population.

Figure 3. Prediction accuracies of three marker types—single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP), haplotypes (HAP), and principal components (PC)—across the 29 models implemented in both MultiGS pipelines in different datasets. (A) the wheat2000 dataset, (B) the maize6000 dataset, and (C) the flax287 dataset.

Figure 3. Prediction accuracies of three marker types—single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP), haplotypes (HAP), and principal components (PC)—across the 29 models implemented in both MultiGS pipelines in different datasets. (A) the wheat2000 dataset, (B) the maize6000 dataset, and (C) the flax287 dataset.

The effect of marker type was most pronounced in the flax287 dataset, which represents a true APP scenario. Across all three traits, HAP markers substantially improved prediction accuracies relative to both SNP and PC markers. HAP-based models improved PA by 0.12–0.26 compared with SNPs and by 0.24–0.28 compared with PCs, depending on trait. SNP-based models ranked second, while PC-based predictions consistently showed the lowest accuracy and greater variability across models.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that haplotype markers provide a more informative genomic representation than single-marker or PC-based encodings when population structure is strong and training and target populations differ. By preserving local LD patterns and multi-allelic information, haplotype-based markers improve both prediction accuracy and robustness in across-population genomic prediction, particularly in small or structured breeding populations such as flax.

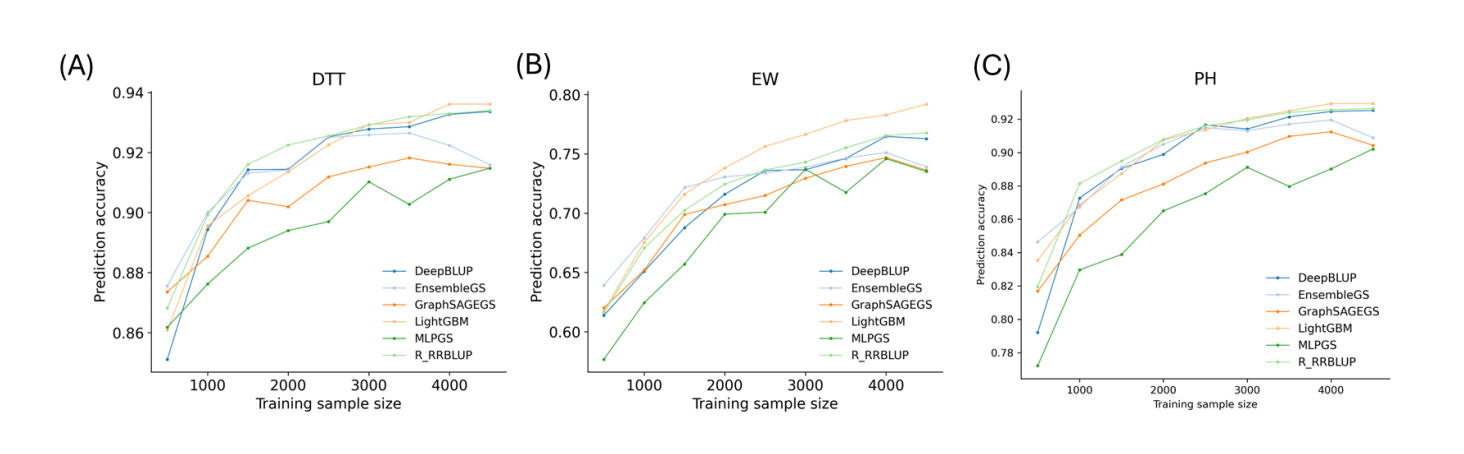

Effect of Training Population Size on Prediction AccuracyThe relationship between PA and training population size was evaluated using the maize6000 dataset, which provided training sets ranging from 500 to 4500 individuals. Seven representative models were assessed, including linear (R_RRBLUP), ML (LightGBM), DL (MLPGS, DNNGS, GraphSAGEGS), and hybrid approaches (DeepBLUP, EnsembleGS). Across all three traits (DTT, EW, and PH), PA increased consistently with training population size, with rapid gains observed between ~500 and 2500 samples and continued improvement at larger sizes (Figure 4).

Although deep learning models are often assumed to require large datasets, linear models also benefited from increased sample size. R_RRBLUP achieved its highest accuracies at the largest training sizes and, in several cases, matched or exceeded DL models beyond 4000 samples. LightGBM showed strong scalability and frequently performed best for traits with pronounced nonlinear components, particularly EW. The hybrid model DeepBLUP exhibited stable gains comparable to R_RRBLUP, whereas other DL models generally underperformed relative to the linear baseline across most training sizes. Overall, these results demonstrate that increased training population size leads to continued improvements in genomic prediction accuracy across all model classes, regardless of model complexity.

Figure 4. Prediction accuracies of three traits in the maize6000 dataset across varying training sample sizes. The full dataset contained 5831 samples, from which 4,664 lines (80%) were randomly selected as the training population and 1167 lines (20%) as the test set. A random subset of 10,000 SNPs was used as markers. From the 4,664 training lines, subsets of different sizes were randomly sampled and used to predict the fixed set of 1167 test samples. Panels show results for: (A) days to tassel (DTT); (B) ear weight (EW); and (C) plant height (PH).

Figure 4. Prediction accuracies of three traits in the maize6000 dataset across varying training sample sizes. The full dataset contained 5831 samples, from which 4,664 lines (80%) were randomly selected as the training population and 1167 lines (20%) as the test set. A random subset of 10,000 SNPs was used as markers. From the 4,664 training lines, subsets of different sizes were randomly sampled and used to predict the fixed set of 1167 test samples. Panels show results for: (A) days to tassel (DTT); (B) ear weight (EW); and (C) plant height (PH).

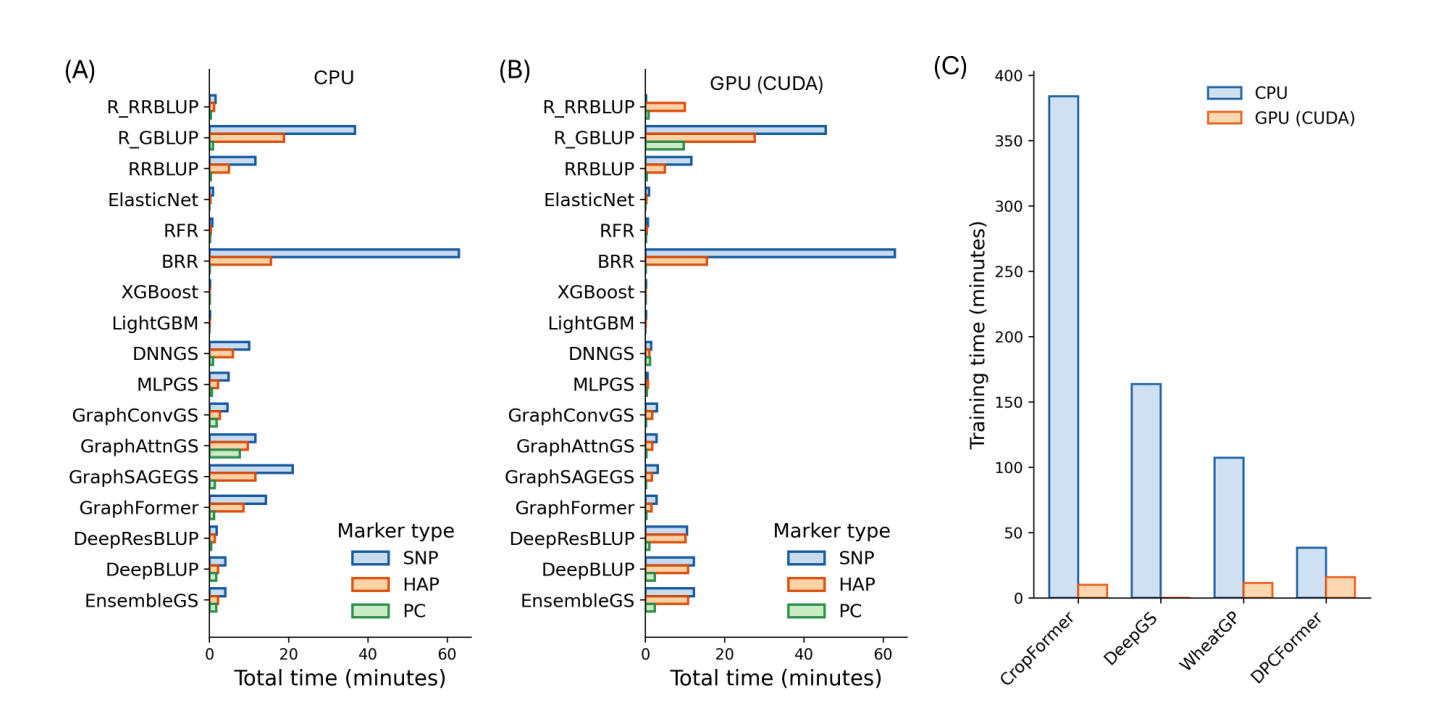

Using the maize6000 dataset, we compared the computational efficiency of 17 models implemented in MultiGS-P across linear, ML, DL, and hybrid categories under both CPU and GPU environments (Figure 5A,B). In addition, four previously published DL models were evaluated separately (Figure 5C). Total runtime represents the average training time across three traits.

Under CPU-only conditions, most linear and ML models completed training within seconds to a few minutes across marker types, with RR-BLUP, ElasticNet, RFR, XGBoost, and LightGBM showing consistently short runtimes. However, Bayesian linear models (BRR) and R_GBLUP required substantially longer runtimes, in some cases exceeding those of several DL models, reflecting the computational cost of iterative Bayesian sampling and mixed-model variance estimation rather than model complexity per se.

Figure 5. Runtime performance of deep learning models compared with linear and machine-learning models under CPU and GPU environments on the high-performance computing server. A total of 17 models implemented in MultiGS-P and four previously published tools were evaluated using the maize6000 dataset. Total time represents the average training time required for model fitting of each trait. All benchmarks were conducted across three traits. (A) and (B) Runtime (minutes) for 17 models under CPU and GPU environments, respectively. (C) Runtime (minutes) for four previously published deep learning models using SNPs.

Figure 5. Runtime performance of deep learning models compared with linear and machine-learning models under CPU and GPU environments on the high-performance computing server. A total of 17 models implemented in MultiGS-P and four previously published tools were evaluated using the maize6000 dataset. Total time represents the average training time required for model fitting of each trait. All benchmarks were conducted across three traits. (A) and (B) Runtime (minutes) for 17 models under CPU and GPU environments, respectively. (C) Runtime (minutes) for four previously published deep learning models using SNPs.

DL models implemented in MultiGS-P showed moderate CPU runtimes, with fully connected architectures generally faster than graph-based models, which incurred additional overhead due to graph construction and message passing. Hybrid models exhibited intermediate runtimes and remained computationally feasible for routine use.

GPU acceleration substantially reduced training time for most DL models, with reductions ranging from ~40% to more than 90%. However, GPU acceleration provided little benefit for classical linear and ML models and, in some cases, increased runtime due to data-transfer overhead and workflow initialization cost. Among previously published CNN-based DL models, CPU runtimes were markedly longer than those of all MultiGS-P models; although GPU acceleration reduced their training time when supported, they remained computationally more demanding. While absolute runtimes were influenced by system load at the time of benchmarking, relative trends across model classes were consistent. These results indicate that MultiGS-P achieves practical computational efficiency for large-scale genomic prediction while supporting a diverse range of DL and hybrid models.

The primary objective of MultiGS was not to advocate a single superior genomic prediction model, but rather to provide a unified, practical, decision-support framework for evaluating and deploying multiple GS methodologies under realistic breeding scenarios. Across wheat2000 and maize6000 datasets, where training and test sets were randomly sampled from the same population, DL, hybrid, and ensemble models implemented in MultiGS achieved PAs comparable to RR-BLUP and frequently exceeded those of GBLUP. These results are consistent with previous reports showing that non-linear models can match or marginally improve upon linear mixed models when the training population size is sufficiently large and population structure is well matched between training and testing sets [10,36].

From a breeding perspective, however, such within-population evaluations reflect an optimistic assessment of prediction performance. Because training and test sets are drawn from the same population, these evaluations closely resemble cross-validation (Table S4) and do not fully capture the challenges of predicting truly new breeding lines in deployment. By contrast, the flax287 dataset provides a realistic across-population prediction case, characterized by a small training population and evaluation in genetically narrow biparental populations. This setting more closely reflects operational breeding programs, where PA often declines sharply due to population divergence, limited training data, and changes in LD patterns [5,37]. Under these conditions, linear and BLUP-integrated hybrid models provide stable and reliable performance, whereas the benefits of DL models are more context dependent.

The training population size analysis further supports these observations. Using the maize6000 dataset, prediction accuracies increased monotonically with training population size across all model classes, with the largest gains occurring between approximately 500 and 2500 individuals (Figure 4). Notably, linear models such as RR-BLUP continued to improve with increasing sample size and often matched or exceeded deep learning models even at the largest training sizes, highlighting that data availability remains a dominant driver of prediction accuracy regardless of model complexity.

Model Robustness Under Across-Population PredictionResults from the flax287 dataset highlight a clear distinction between model capacity and model robustness. Classical linear models, including RR-BLUP, BRR, and Bayesian regressions, provided stable and interpretable baseline performance across traits, particularly for DTM, where prediction accuracy was uniformly low. This stability underscores the continued relevance of linear mixed models in GS, especially for traits dominated by additive genetic effects and for scenarios with limited training data [1,3].

However, many pure DL architectures exhibited high variability and, in some cases, poor or negative predictive performance in flax, reflecting well-known limitations of high-capacity models under small sample sizes and pronounced training–test distribution shifts. These results caution against indiscriminate applications of DL models in breeding programs without careful consideration of population structure and data availability.

Notably, a subset of DL and hybrid models had improved robustness under this challenging setting. Graph-based models (GraphSAGEGS, GraphFormer) and BLUP-integrated hybrids (DeepBLUP, DeepResBLUP) benefited from stronger inductive biases toward biologically meaningful structure. Graph-based models operate on sample-level genetic relationship graphs rather than raw marker effects, making predictions less sensitive to population-specific LD patterns and allele-frequency shifts. In particular, the inductive neighborhood aggregation in GraphSAGEGS facilitates transfer of information to genetically divergent populations. Similarly, BLUP-integrated hybrids preserve additive genetic effects by anchoring predictions to a linear RR-BLUP component, allowing the deep network to model only residual nonlinear signals. Together, these design features contribute to enhanced robustness under across-population prediction.

Comparison with Previously Published Deep Learning ModelsAlthough DL models have been applied to GS since 2018 [10], beginning with convolution-based models such as DeepGS [9], subsequent developments have expanded to recurrent, attention-based, transformer, and graph-based architectures [15,16,19,20,38–40]. Across studies, reported prediction accuracies are generally comparable to, but not consistently higher than, those obtained with linear baselines such as RR-BLUP, particularly when training populations are large and marker density is high. Despite methodological advances, many published DL-based GS tools face practical limitations that hinder reproducibility and routine adoption, including incomplete documentation, rigid input requirements, discrepancies between published descriptions and available code, and the lack of standardized workflows for preprocessing and evaluation. In addition, computational constraints often necessitate fixed input dimensions, leading to ad hoc SNP subsetting or padding [17,20,22].

In contrast, MultiGS imposes no explicit restrictions on marker number and instead emphasizes biologically informed and computationally efficient marker types. Haplotype and PC encodings reduce feature dimensionality while preserving linkage disequilibrium and population structure, improving training efficiency without arbitrary feature selection. Graph-based models in MultiGS further reduce complexity by operating on sample-level graphs rather than marker-level graphs.

Across wheat2000, maize6000, and flax287 datasets, DL and hybrid models implemented in MultiGS achieved prediction accuracies comparable to or exceeding those of previously published DL tools. While previously published models performed well under within-population validation, their performance declined in the flax across-population scenario. Conversely, several MultiGS hybrid models showed greater stability across datasets and prediction settings. These results suggest that architectural complexity alone is insufficient for robust genomic prediction; instead, models that integrate additive genetic effects with DL refinement and emphasize generalizability are better suited to realistic breeding scenarios. By providing a unified, configurable, and well-documented framework, MultiGS addresses key limitations of existing DL-based GS tools and facilitates fair benchmarking and practical deployment.

Computational Efficiency and Breeding DeploymentIn practical breeding pipelines, computational efficiency is a critical but often underappreciated factor. Most DL and hybrid models implemented in MultiGS required less computational time than previously published DL approaches while delivering comparable predictive accuracy. This efficiency enables frequent model retraining as new phenotypic data becomes available and facilitates large-scale benchmarking across traits, populations, and marker types.

From an operational perspective, when PA is similar, reduced computational burden becomes a decisive advantage. The ability to execute MultiGS models under CPU-only environments further lowers barriers to adoption, particularly for public breeding programs with limited computational infrastructure. These considerations are essential for translating methodological advances into routine breeding practice.

Implications for Model Selection and Tool DevelopmentTaken together, the results reinforce several key principles for genomic selection. First, no single model is universally optimal across traits or prediction scenarios. Second, classical linear models remain strong and reliable baselines, particularly for across-population prediction. Third, DL models can offer advantages for certain traits and datasets, but their success depends strongly on training population size, genomic architecture, and model design. Hybrid and ensemble approaches consistently provide the most stable improvements, combining the interpretability of linear models with the flexibility of nonlinear learning.

The primary contribution of MultiGS lies in enabling breeders and researchers to explore these trade-offs systematically within a unified framework. By integrating R- and Python-based models, supporting multiple marker types, and providing standardized evaluation pipelines, MultiGS facilitates informed model selection rather than relying on a single methodology. This design aligns closely with actual breeding workflows, where adaptability, robustness, and computational practicalities are as important as peak PA.

Marker type also emerged as a critical and often underappreciated factor influencing prediction accuracy. Across both maize and flax datasets, haplotype-based markers consistently matched or exceeded SNP-based predictions and outperformed PC-based predictions in across-population settings (Figure 3). These results indicate that preserving local LD and multi-allelic information can improve robustness and accuracy, particularly when training populations are limited or genetically divergent. Consequently, effective genomic selection requires joint consideration of marker representation, model architecture, and training population characteristics rather than optimization of predictive models alone.

Limitations and Future DirectionsSeveral limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, benchmarking in the wheat2000 and maize6000 datasets relied on random within-population training–test splits, which approximate cross-validation and may overestimate prediction performance relative to actual breeding deployment, particularly for DL models. The flax287 dataset provided a true across-population prediction scenario, but its small training population limited the evaluation of high-capacity DL architectures.

Second, most phenotypic data used in the present benchmarks were derived from single or limited environments and thus do not explicitly capture genotype-by-environment (G × E) interactions, which are pervasive in real-world breeding programs. G × E can substantially reduce prediction accuracy when models trained in one environment are applied to others, and its effects may differ between traditional GS models and more flexible DL architectures that can implicitly model complex and nonlinear responses.

Future studies using larger and more diverse populations, combined with systematic across-population and across-environment validations, are warranted to better define conditions under which DL models provide consistent advantages. The MultiGS framework is readily extensible to multi-environment genomic selection through the integration of environmental covariates, reaction-norm formulations, or multi-environment mixed models, enabling joint modeling of genetic main effects and G × E interactions.

In addition, the current MultiGS implementation focuses on single-trait prediction, whereas many breeding programs target correlated traits evaluated across multiple environments; extending the framework to multi-trait and multi-environment models should be incorporated in future iterations. Finally, although graph-based and hybrid DL models showed increased robustness in some settings, their performance remained sensitive to marker type and population structure, highlighting the need for improved hyperparameter optimization, automation, and resource management to support stable and scalable deployment in practical breeding pipelines. Future development will also support matrix-based, scored marker inputs beyond VCF, enabling direct use of breeder-curated genotype tables and alternative marker systems that are not readily convertible to VCF.

MultiGS was developed to support both methodological researchers and applied breeding programs by enabling transparent benchmarking as well as routine genomic prediction within a unified framework. By integrating traditional statistical models, ML methods, and modern DL architectures into a standardized workflow, MultiGS provides a practical platform for evaluating and deploying genomic selection across diverse crops and prediction scenarios.

Across wheat2000, maize6000, and flax287 datasets, the results showed that classical linear models such as RR-BLUP remain strong and reliable baselines, while selected DL, hybrid, and ensemble models implemented in MultiGS achieve comparable or superior PA under appropriate conditions. The flax across-population case study demonstrated that prediction robustness, rather than peak accuracy under idealized validation, remains the primary challenge for actual breeding applications. In this context, graph-based and BLUP-integrated hybrid models exhibited more stable generalization than many high-capacity DL architectures.

In addition, MultiGS DL and hybrid models delivered competitive accuracies with lower computational cost than previously published DL tools, supporting their suitability for routine use in breeding programs. In general, no single model is universally optimal across traits or populations. MultiGS addresses this challenge by providing a flexible, efficient, and extensible platform that enables breeders and researchers to make informed, scenario-specific decisions when applying genomic selection in practice.

The following supplementary materials are available online: Figure S1. Architectures of two fully connected network and four graph-based deep learning models for genomic selection: (A) DNNGS, (B) MLPGS, (C) GraphConvGS, (D) GraphAttnGS, (E) GraphSAGEGS, and (F) GraphFormer; Figure S2. Architectures of three hybrid genomic selection models that integrate linear and deep learning components. (A) DeepResBLUP, (B) DeepBLUP and (C) EnsembleGS; Figure S3. Multidimensional scaling (MDS) analysis based on the genomic relationship matrix (GRM) for 278 training lines (flax287) and 260 test lines from three biparental populations, showing pronounced genetic structure between the two sets; Table S1. Linear and machine learning models implemented in MultiGS-R; Table S2. Summary of eight linear and machine learning models implemented in MultiGS-P; Table S3. Default hyperparameter settings for the machine learning and deep learning models implemented in MultiGS-P; Table S4. Genetic diversity and population differentiation between training and test sets across three datasets; Table S5. Prediction accuracies of five traits across models implemented in MultiGS-P, evaluated using a wheat training set of 1,600 accessions and a testing set of 400 randomly selected accessions genotyped with a randomly selected set of 10,000 SNP markers; Table S6. Prediction accuracies of three traits across models implemented in MultiGS-P, evaluated using a maize training set of 4,664 lines and a testing set of 1,167 randomly selected lines, and genotyped with 10,000 randomly selected single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), 5,439 haplotype (HAP) or 313 principal component (PC) markers; Table S7. Prediction accuracies of three traits across models implemented in MultiGS, evaluated using a flax training set of 278 accessions from a core collection and a testing set of 260 biparental inbred lines, with 7,363 haplotype markers derived from 33,895 common SNPs.

All datasets used in this study were obtained from publicly available sources, as described in Materials and Methods. The MultiGS software and associated utility programs are freely available on GitHub (https://github.com/AAFC-ORDC-Crop-Bioinformatics/MultiGS).

FMY: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, software development, original draft preparation. SC: conceptualization, funding acquisition, DNA preparation for SNP genotyping, data curation, manuscript review and editing. BT: conceptualization, funding acquisition, data curation, manuscript review and editing. JJZD: software development. CZ, JJZD, PL and KJ: formal analysis, visualization, data curation, manuscript review and editing.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This research was supported by the Genome Canada 4D Wheat project and the Sustainable Canadian Agricultural Partnership AgriScience Cluster (SCAP-ASC) projects: (1) Diversified Field Crop Cluster Activity 5A (SCAP-ASC-05), and (2) Wheat Cluster Activity 12A (SCAP-ASC-08).

We thank Liqiang He for reviewing the draft manuscript and providing valuable comments and suggestions.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

You FM, Zheng C, Zagariah Daniel JJ, Li P, Tar’an B, Cloutier S. MultiGS: A Comprehensive and User-Friendly Genomic Prediction Platform Integrating Statistical, Machine Learning, and Deep Learning Models for Breeders. Crop Breed Genet Genom. 2026;8(1):e260004. https://doi.org/10.20900/cbgg20260004.

Copyright © Hapres Co., Ltd. Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions